Antidepressants, so the story goes, work by boosting levels of serotonin. The most widely prescribed class, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, stop the removal of this neurotransmitter from the gaps between neurones. While there is endless debate on the precise role of serotonin in depression (too much ink has been already been spilled), this transmitter is clearly involved in regulating mood and emotion.

SSRIs are an effective treatment for depression, but their benefit above placebo is smaller than we’d like. They seem to be better at certain depressive symptoms, particularly anxiety, than others. Many people report characteristic side-effects which can be intolerable. They are associated with initiation anxiety and nausea, and longer-term sexual dysfunction. I’ve written about difficulties faced by patients when trying to stop these medications - withdrawal from SSRI can result in a syndrome of unpleasant symptoms like ‘brain zaps’, dizziness and nausea.

Serotonin’s role in mood-regulation may lead to restriction in the range of emotion, sometimes called blunting or numbing. Some people would have you believe antidepressants’ mechanism of action is through inhibiting emotions. I’ve never been sold on this theory - not all antidepressants act on serotonin or cause these emotional side-effects.

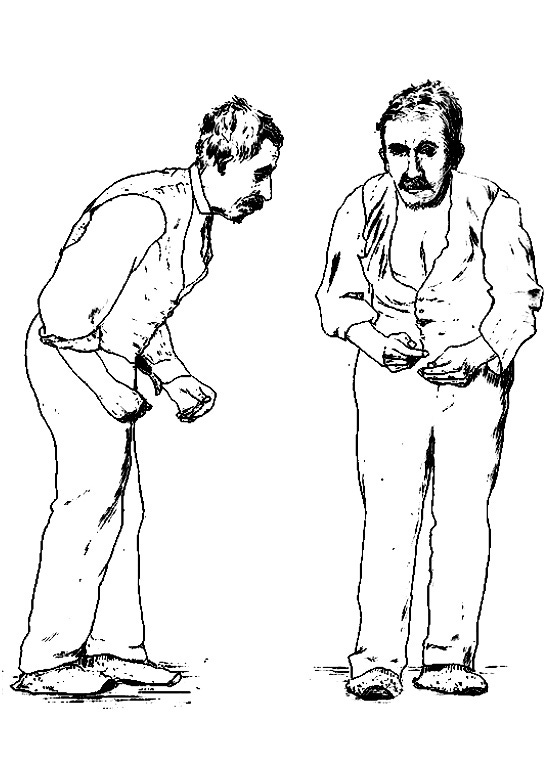

Depression, we all know, is a heterogenous condition. Some patients experience prominent anxiety and might respond well to SSRIs. Some patients at the severe end experience psychosis and are best treated with a combination of antidepressant (serotonergic) and antipsychotic (dopamine receptor blockade). Some patients experience episodes of low mood interspersed by episodes of elevated mood (bipolar depression) and respond better to mood stabilisers like lithium.

There is another group of depressed patients who seem to have marked impairment in motivation, inability to experience joy (anhedonia) and low energy. Theoretically, we might expect these patients to respond less to SSRIs and more to drugs targeting the dopamine system, which is closely linked with reward. We already have an antidepressant with dopaminergic activity called bupropion, though frustratingly in the UK it is licensed only for smoking cessation rather than depression.

Having new classes of antidepressant which target dopamine might be helpful for the subgroup of patients that don’t respond well to conventional antidepressants - sometimes called, a little uncharitably, treatment resistant. Looking beyond serotonin might also increase the range of symptoms which can be effectively treated.

By happy coincidence we already have groups of medications designed for the exact purpose of increasing dopamine activity, drugs for Parkinson’s disease. Dopamine agonists are medications which increase activation of dopamine receptors. One dopamine agonist in particular, pramipexole, has previously shown promise in small trials for both unipolar and bipolar depression.

This week, The Lancet Psychiatry published a largish (n=150) randomised placebo-controlled double-blind trial of pramipexole as augmentation (added-on to usual treatment) for treatment-resistant depression. If you’re a psychiatrist treating patients with depression, I suggest you start learning how to spell and pronounce this medication, because the results are impressive.

PAX-D

The study, called PAX-D, was set up from the University of Oxford1 and launched in 2021. It was a multi-centre trial, recruiting patients from across England. To be eligible, participants had to be diagnosed with depression, with at least moderate scores on the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology. They had to be treatment resistant meaning a lack of response to at least two antidepressants at therapeutic doses within the current episode. Participants were ineligible if they had ever been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, psychosis (including psychotic depression) or Parkinson’s disease. They couldn’t be prescribed an antipsychotic (this has the opposite effect to dopamine agonists) or have ‘serious suicide or homicide risk’.

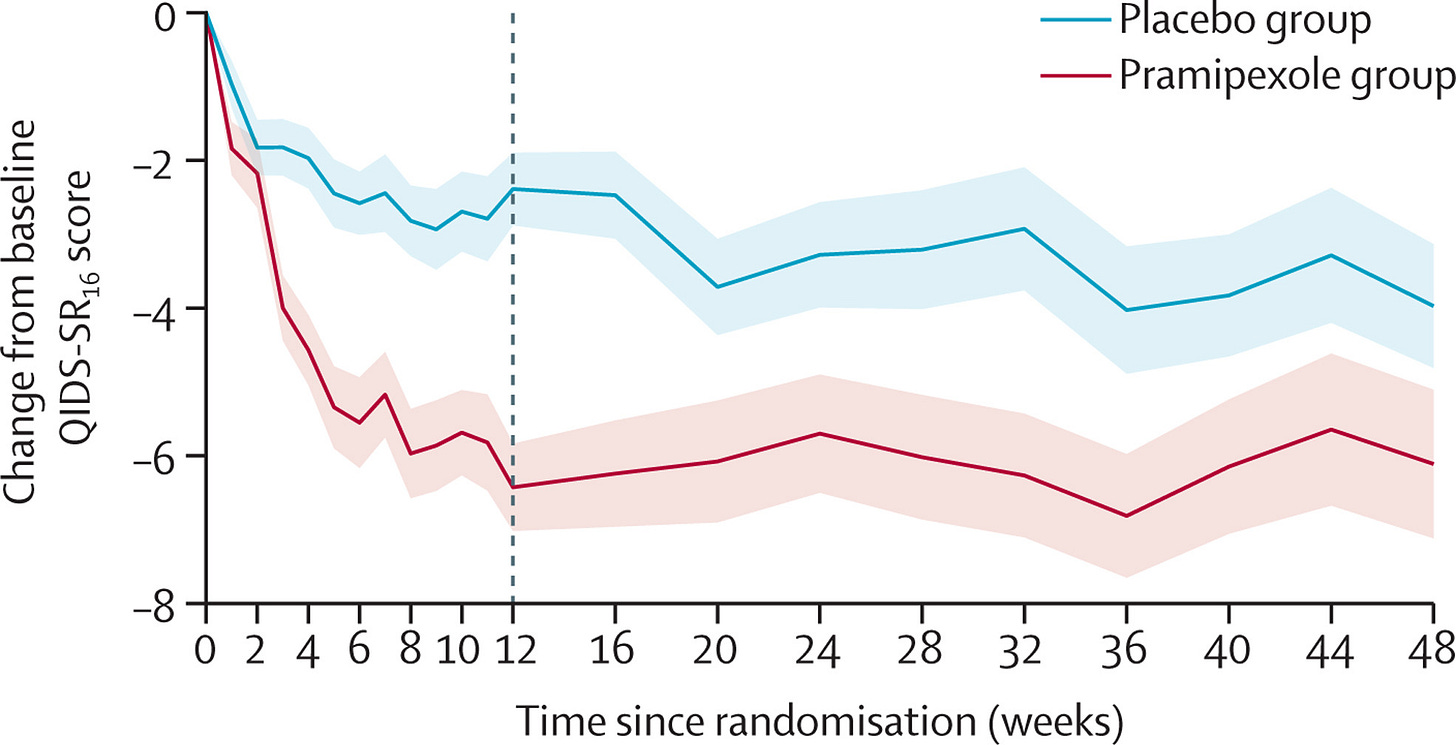

After being randomised to either placebo or pramipexole, the main outcome measure was the QIDS at 12-weeks. Importantly (depression trials are often criticised for being short-term) the effectiveness was measured up to 48-weeks. The study wanted to determine whether this intervention was effective at treating depressive symptoms and whether its side-effects were tolerable.

Before we get into the results, let me set the scene. We know that drug development is hard. Most candidates fail. The costs are huge and the rewards uncertain. Most compounds which look promising in small trials are duds. Most effect sizes shrink or disappear completely when tested in an adequately powered sample.

The bureaucratic hurdles in conducting clinical research in the UK are well known, to the extent that even completing a trial of this size is an impressive; an immense effort from many researchers, patients, and clinicians. A well-conducted trial significantly contributes to medical knowledge, even if the results are negative. However, for PAX-D the results weren’t negative, they were better than anyone could reasonably expect.

The primary outcome is plotted below.

The effect size is big enough to make me nervous I’ve missed a glaring error in the study methodology. But their analysis plan was straightforward and pre-specified. The protocol was published in advance. Sensitivity and additional analyses are provided. Maybe the biggest issue identified is that around 3/4 of participants correctly guessed their treatment allocation, threatening the ‘double-blind’ design. I do predict that, simply due to regression toward the mean, subsequent trials of pramipexole will have smaller effects.

Of course, in medicine, there is no free lunch. All treatments have side-effects and we should expect those with large effects to have more severe side-effects. Adverse events were similar across groups 99% in pramipexole versus 97% in placebo, as were serious adverse events (5% versus 3%). However, there was a higher rate of dropouts due to intolerance (20% versus 5%). There were two cases of impulse control disorder in the treatment group and none in the controls. These impulsivity side-effects, which can result in compulsive gambling, excessive spending or hypersexuality, are a known complication of dopamine agonists.

Psychiatrists who spend their time prescribing dopamine-blocking meds for bipolar disorder and psychosis will naturally feel nervous about a medication that increases dopamine activity. Perhaps related to this, a sister trial, PAX-BD, which examined pramipexole for bipolar depression, was terminated early due to recruitment problems. PAX-BD aimed to recruited 290 participants but only randomised 39. In this underpowered sample, there were hints at an effect against depressive symptoms (not statistically significantly) while the drug did cause a statistically significant increase in hypomanic symptoms.

Answers and questions

PAX-D gives us a clear answer: pramipexole is an effective add-on to other antidepressants in people with chronic long-term depressive disorders which have not responded to treatment. The most surprising aspect of the trial was the magnitude of this effect.

However, like many research findings, it provokes a flurry of new questions. Could pramipexole work as a monotherapy? Will it work even better in patients with less chronic problems? Where is its place in the treatment algorithm? Almost half of the trial participants were prescribed an SSRI, is it this combination of serotonin plus dopamine action that really makes the difference? Like bupropion, could it be useful for patients who cannot tolerate SSRIs due to emotional numbing or sexual dysfunction?

Most provocatively: could it be more effective than the antidepressants already at our disposal?

I suspect psychiatrists seeing patients with difficult to treat depression will start thinking about pramipexole, particularly for anhedonic symptoms. Its precise role in clinical practice should become clearer with further research in the coming years.

Takeaways

This study has several take-home-messages at different levels of analysis. Firstly it consolidates the dopaminergic system as a therapeutic target in depression. As a corollary to this, depression isn’t just about serotonin. And antidepressant action probably doesn’t rely on restricting normal emotion.

Taking a step back, the trial is another success story for drug repurposing. Pramipexole was licensed for Parkinson’s disease, its side-effect profile was known, it was ‘oven ready’. A mixture of clinical and theoretical reasoning led to it being an antidepressant candidate - and it worked! How many more medications are on the shelf, waiting to be tested for the right indication?

Finally, this trial was funded by NIHR, effectively part of the UK government. For repurposing studies without pharmaceutical financial incentives, we need university research departments to propose plausible candidates and for government agencies to fund the studies that determine effectiveness. As a country we need to back this type of research, because the UK does it well.

Ultimately, I think this new treatment will have tangible improvements for people suffering from chronic depression. Let’s take these victories in psychiatry where we can.

COI the Chief Investigator Professor Mike Browning is an examiner for my doctorate - I’m sure he’d prefer me writing my thesis rather than this blog

I would urge extreme caution with dopamine agonists, especially if there is a view for using with recurrent depressive disorder - they used to be 1st line treatment in restless leg syndrome but are no longer recommended. Dopamine agonists, at even low dosages of .125mg once/day, can cause augmentation within a couple of years. You might want to look into this. Something like 60% of RLS patients prescribed a dopamine agonist will develop augmentation whereby the DA causes worsening severity of RLS (starts earlier, affects other limbs, causes pain) necessitating the patient to increase the dose and thereby making the RLS worse. Augmentation can cause complete insomnia and lead to all the inevitable problems that come with sleep deprivation. There is also dopamine agonist withdrawal syndrome too.

Given that nearly all antidepressants can make RLS worse (I think bupropion and trazadone are the only ones considered "safe" to prescribe with coexisting RLS), quetiapine is becoming quite notorious for causing RLS and those with bipolar disorder given quetiapine seem to be particularly likely to develop RLS after beginning treatment, and DAs ability to increase motivation...there is still quite a bit of unlocking to do here.

I would urge treating physicians to enquire about symptoms of RLS, and family history, before beginning treatment, and keep asking if RLS has developed during treatment. I'm not aware of any data looking at whether RLS and augmentation can develop in those without a history of RLS. Although RLS has been treated as a bit of a joke in the past it is a deeply unpleasant condition, augmentation is appalling, and withdrawal of DAs, especially cold turkey, is a horrifying experience. Pregabalin is now the gold standard for RLS.

Pramipexole can cause quite bad nausea which can be avoided by taking at bedtime. DAs can also cause suicidal ideation and planning by very violent and disturbing means, as well as delusions, hallucinations, and paranoia.

Nice article! I may dig into the PAX-D trial at some point as the findings are very intriguing.