It is an art of no little importance to administer medicines properly: but, it is an art of much greater and more difficult acquisition to know when to suspend or altogether to omit them.

The skill of appropriately stopping treatment is an inherent part of medical practice and should be in the toolkit of every prescriber. Some specialties are famous for it. You may have heard of the geriatrician’s scalpel; not a blade but a humble pen, used to score out unnecessary meds off the drug charts of elderly patients.

Acute medicine has established procedures for treating withdrawal from drugs like alcohol or GHB (in which abrupt discontinuation can be fatal). Addiction psychiatrists are well versed in slowly stopping opioids. Withdrawal effects aren’t just seen in psychotropics, many medications from steroids to anti-hypertensives have to be slowly reduced in dose over time to prevent a rebound effect.

The opening Pinel quote appears in the preface of the Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines, showing that deprescribing is as old as psychiatry itself. For a skill that should be universal, discontinuing medication (particularly antidepressants) has become a controversial topic. Part of the blame must lie with mainstream psychiatry which seems to have either downplayed or ignored problems of stopping antidepressants.

Antidepressant discontinuation symptoms

As recently as 2018, the Royal College of Psychiatrists stated that ‘in the vast majority of patients, any unpleasant symptoms experienced on discontinuing antidepressants have resolved within two weeks of stopping treatment’. Until 2019, guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) stated that discontinuation symptoms were usually mild and self limiting over about one week.

This clearly wasn’t the full story. If you are a doctor treating patients with depression (or even if you speak with your friends who take antidepressants, about 1 in 6 of us do), you will hear stories about how difficult it can be to stop these medications and of unpleasant effects when doses are missed.

The latest meta-analysis estimates the rate of discontinuation symptoms at roughly 1/3 in those who stop their antidepressant (for comparison, this is about double the rate of discontinuation symptoms when stopping an inert placebo). In approximately 3% of patients, these symptoms are rated as severe. While 3% is a small proportion, given that more than 7 million people in England are prescribed antidepressants, it is still a big issue. Most commonly, patients report flu-like symptoms, nausea, dizziness, paraesthesia (sometimes described as ‘brain-zaps’ or ‘electric shocks’), and anxiety. The worst culprits tend to be antidepressants with the shortest half-lives (meaning the level in the body is quickly metabolised and eliminated) such as paroxetine or venlafaxine.

Since the psychiatric establishment did not acknowledge the problem of stopping antidepressants, far less offer assistance, these patients had to effectively set-up their own support groups - for example, Surviving Antidepressants. Patients relying on peer-support for stopping psychiatric medications is a sad inditement. In many cases, they may even have been told that withdrawal symptoms were the first indications of depressive relapse.

Maudsley (De)Prescribing Guidelines

The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry were launched in 1994 and are now in their 14th edition. They are a widely used reference for psychiatric prescribing, in the UK and beyond. Last year, the first Deprescribing guidelines was published by Professor David Taylor and Dr Mark Horowitz. David Taylor is the Chief Pharmacist at the Maudsley and has been writing these prescribing guidelines since they began. He is a member of the British Association for Psychopharmacology and is the only pharmacist to be made honorary fellow of the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

Mark Horowitz, I think it’s fair to say, has had a less conventional journey. He did his PhD with Professor Carmine Pariante at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, doing lab work on cellular models of depression. He has since swung in an almost opposite direction, working at University College London with Professor Joanna Moncrieff (whose views on psychiatric medication are very much outside of the mainstream).

What’s really remarkable is that both these clinicians became aware of antidepressant withdrawal when they experienced it for themselves. Then after working together clinically, they decided to fill the gap by producing their own guidelines. Again, it reflects poorly on psychiatry that we had to have two academics (one very much established, one up and coming) to personally experience these symptoms before we took them seriously. Mark in particular pays homage to the various patient-led insights into antidepressant withdrawal that helped inform his own practice.

The Deprescribing Guidelines goes into detail on the half-lives and withdrawal symptoms associated with various meds, grouped into categories of antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and Z-drugs. They provide tapering doses and schedules for each individual drug.

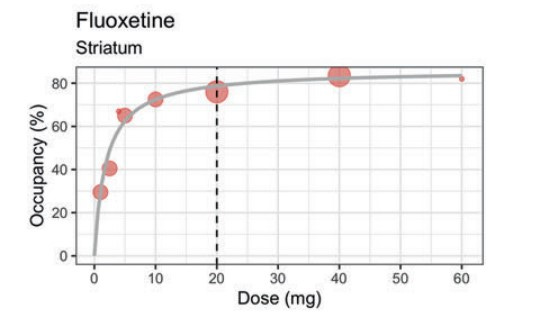

The ‘secret sauce’ of these guidelines is hyperbolic tapering; as you get to lower doses of the medication, the dose-reductions become smaller. The underlying logic is that at higher doses, receptors in the brain are saturated with the drug, while at lower doses, more receptors are available to bind, so the dose changes are more significant (illustrated below with the antidepressant fluoxetine).

Instead of recommending a linear dose reduction over weeks-months of say:

40mg → 30mg → 20mg→ 10mg → 5mg → 0mg

A much slower - hyperbolic- dose reduction is advised over a period of months-years, an example from the guidelines of a ‘moderate’ taper for fluoxetine:

40mg → 20mg → 15mg → 10mg → 7mg → 5mg → 3.8mg → 3mg→ 2.4mg → 1.92mg → 1.5mg → 1.2mg → 0.96mg → 0.72mg → 0.56mg → 0.4mg → 0.24mg → 0.12mg → 0mg

Looking at that above dosing, many prescribers would raise a skeptical eyebrow. The lowest dose of fluoxetine tablets is 10mg, so 0.12mg is 1% of this - some would describe this as homeopathic, biologically inert. It means that to get these tiny doses, patients are advised to use diluted liquid fluoxetine. For other medications getting a small enough dose might involve opening a capsule and counting out the beads. As far as I know, there is no empirical evidence to show whether these very slow reductions are necessary or whether such tiny doses have a noticeable effect in a placebo-controlled experiment. But this is an emerging area, so we need time for research to be done.

These general principles behind stopping - doing it over a long period and making smaller dose adjustments at lower doses - seems logical. It is also crucial to acknowledge that a minority of patients will get severe withdrawal symptoms and may need even longer, slower tapering.

Backlash

Judging from sales (twice the rate of the Prescribing Guidelines) and Amazon reviews, the Deprescribing Guidelines have been a success. Positive reaction from the British Journal of General Practice and NHS England suggest the guidelines were much needed. It has been incorporated into guidance for GPs in Australia.

However, the praise hasn’t been universal. There has been criticism that Mark Horowitz did not declare a conflict of interest, that he is the co-founder of a USA-based private deprescribing service, Outro. I understand he runs a specialist deprescribing clinic within the NHS too.

I’ve seen a pretty toxic reaction to any of Mark’s media appearances. He himself has said that critics have tried to get him fired. To an extent, the acrimony seems to go both ways, with Mark posting the below cartoon on X, causing a furious reaction among psychiatrists.

I don’t think anyone is their best self on X. I was therefore pleased to see Mark appear on The Thinking Mind Podcast, hosted by Dr Alex Curmi, a Consultant Psychiatrist and former colleague of mine. You get a fuller sense of someone’s view on an hour long conversation than 280 characters - particularly with an interviewer as sensitive as Alex.

Drug-centred dogma

I recommend listening to the episode in full and making up your own mind. Mark gives a fascinating, and remarkably honest, account of his personal journey with antidepressants; being prescribed these for ‘existential’ concerns and the terrible symptoms he experienced on stopping. He emphasised the importance of stressful life events in triggering depressive episodes and warned against the widespread prescription of medication for social problems. Alex, as usual, emphasises the psychological side of mental disorders, giving an example of a patient treated in a tertiary affective disorders service who had received numerous pharmacological trials but never had an adequate course of psychotherapy.

One aspect that concerned me though, was Mark’s reluctance to acknowledge any biological aspect to depression, or the utility of antidepressants. Alex asks Mark whether he recognises that some cases of depression do have a biological component, giving examples of severely unwell patients who may struggle to eat, or become slowed. Mark put the chance of finding biological causes of depression as very, very slim. Instead, he sees depression as ‘normal brains responding to events in life’. In fact, he doesn’t believe the depression has any diagnostic meaning in terms of prognosis or treatment and doesn’t see it as a useful concept. As an analogy, he discussed the example of an abused dog. Obviously we wouldn’t treat this animal with antidepressants, we would give them care until they gradually returned to health.

This gave me pause for thought. I’m sure Mark, as any trainee in psychiatry, will have come across inpatients experiencing severe depressive episodes. Those with early morning wakening, diurnal variation in mood, weight loss, anhedonia. What used to be called melancholia. In some cases, they may experience nihilistic delusions that they themselves are dead, that their internal organs are rotting. They may hear derogatory auditory hallucinations that they are worthless or guilty of a horrendous crime. These patients invariably do not spontaneously remit but often respond well to appropriate medication and in some cases ECT.

I’m sure Mark would have come across patients with bipolar disorder who suffer episodes of depression, interspersed with manic episodes - what used to be called manic depression. These patients tend to respond less well to antidepressants than they do to mood stabilisers, particularly lithium. For these patients it simply isn’t the case that their depressive episodes are caused by a stressful life, any more than their manic episodes are triggered by positive life events.

He may even have come across patients whose depressive episodes appear to have a hormonal trigger and respond to hormonal treatments - such as premenstrual dysphoric disorder or perimenopausal depression. He may have come across patients whose depressive episodes have been triggered by treatment for a medical illness, such as steroids like prednisolone.

Why deny the benefits that antidepressants offer many people? I’ve heard David Taylor describe them as lifesaving. I worry when Mark cites Professor Joanna Moncrieff’s ‘drug-centred’ model of psychiatric medication, critiqued here masterfully by Awais Aftab. This model states, not only that psychiatric medications do not treat the underlying mental disorder, but that they don’t even alleviate symptoms of mental disorders. Instead, psychiatric medications, under this model, are thought to mask symptoms by inducing an abnormal brain state. Joanna Moncrieff’s views on psychiatric medication are completely outside the consensus (‘I’m not convinced that antidepressants have any use’) and seem at odds with those of David Taylor.

Bringing deprescribing in from the cold

Deprescribing is an essential skill for all prescribers and has to become part of mainstream psychiatry. I hope the reputation of Maudsley Guidelines and the authority of someone like David Taylor will help bring it in from the cold. It is a travesty that the problems in stopping antidepressants were ignored for so long and we must congratulate both Mark and David for using their personal experiences to highlight this issue. I’m sure the work they’ve done is already helping many people across the world.

However, we can’t leave deprescribing to the Joanna-Moncrieff-wing of psychiatry. There are dangers in this issue being owned by people who don’t think psychiatric medications have any benefit beyond a kind of temporary numbing of problems. Deprescribing shouldn’t be done in specialist clinics by doctors who are skeptical that medication does any good for anyone - it should be the bread and butter of every working psychiatrist. We need deprescribers to recognise that, for some patients (especially those with recurrent or severe episodes) the benefits of continuing medication may outweigh the benefits of stopping.

I mentioned that in 2018 the Royal College of Psychiatrists stated that in the vast majority of cases, withdrawal symptoms from antidepressants resolved within two weeks. Well the President of the College at the time Dr Wendy Burn faced her own backlash from online patient communities. Instead of dismissing or arguing, she listened to these views and changed the College’s position to the following:

Whilst the withdrawal symptoms which arise on and after stopping antidepressants are often mild and self-limiting, there can be substantial variation in people’s experience, with symptoms lasting much longer and being more severe for some patients. Ongoing monitoring is also needed to distinguish the features of antidepressant withdrawal from emerging symptoms which may indicate a relapse of depression

She also ensured that appropriate information on stopping these medications was published on the College website (both Mark and David contribute as expert authors). Wendy wrote about her experience and how she changed her views in The BMJ. I’m glad we have leaders like Wendy in psychiatry, who are willing to listen to opposing views and adjust their own. It makes me optimistic that deprescribing won’t be left to the mavericks and instead can be made mainstream again.

I came into this note expecting commentary on polypharmacy and instead discovered a nuanced and insightful look into an interesting controversy. Thank you Dr. Reilly!

I have to chime in. Discontinuation of SSRIs and SNRIs is child’s play compared to tapering opioids, benzodiazepines, alcohol, and even nicotine.

Are you seeing psychiatrists who are unaware of how to taper via cross-titration to fluoxetine and then use half-life kinetics if need be? Is there an old guard who does not acknowledge that discontinuation can be a bear for some folks? I finished training in 2016 for reference.

Thank you for this post. A sensible look at side effects of antidepressants is long overdue. There is just no need for doctors and psychiatrists to close this issue down as something that could cast doubt on their status. The research field into pharmaceuticals is never going to be completed, and that’s the nature of it, so I don’t know why some get so defensive when matters like this come up. They’re always going to come up, so it’s always constructive to talk about these issues. Individual differences abound in tolerances to different medications. Personally, I have found fluoxetine to be very effective at eliminating voices and bizarre delusions but less effective at preventing non bizarre delusional paranoia and moderate depression. I have no idea why this is. I know it’s not just a placebo in my case because I was prescribed it when I described symptoms of depression to my doctor. What neither of us realised at the time was that I was floridly psychotic after a head injury which I had no insight about. My hallucinations faded away, with the main persecutory voice actually announcing “I think I’m becoming less controlling”. A few years later I switched to Sertraline and I find this more effective as a mood improver. However, I get really severe vertigo and nausea if I even miss one tablet, so I would definitely need to taper off it gradually if I ever change medication. I’m personally really interested in what works and what doesn’t, and why, but I haven’t come across a clinician who is prepared to cover the topic with any other audience than colleagues, so thank you 🙏