The hard problem of suicide prediction

In the UK, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123, or email jo@samaritans.org, or see samaritans.org. Other international helplines can be found at befrienders.org

Last month, a case of suicide was publicised in the UK media. Tom Pirie, a 26 year old teacher from London took his life in July 2020, the day after a final counselling session. His counsellor apparently rated his risk of completing suicide as ‘low’ the day before his death. On BBC Breakfast, the presenter Dan Walker says to his father:

That must be devastating for you to know that he was sat in the chair with someone who could have helped him and somehow the system didn’t work.

Every instance of suicide is a tragedy. Loved ones may be left replaying last meetings in their minds; could I have said or done something different? Healthcare professionals can have similar responses.

Suicide is recognised by the WHO as preventable. Yet suicide prediction is a fundamentally hard problem. Below I will describe why it is so challenging, and why so many people who complete suicide are categorised as 'low risk'.

Suicide is a major public health issue

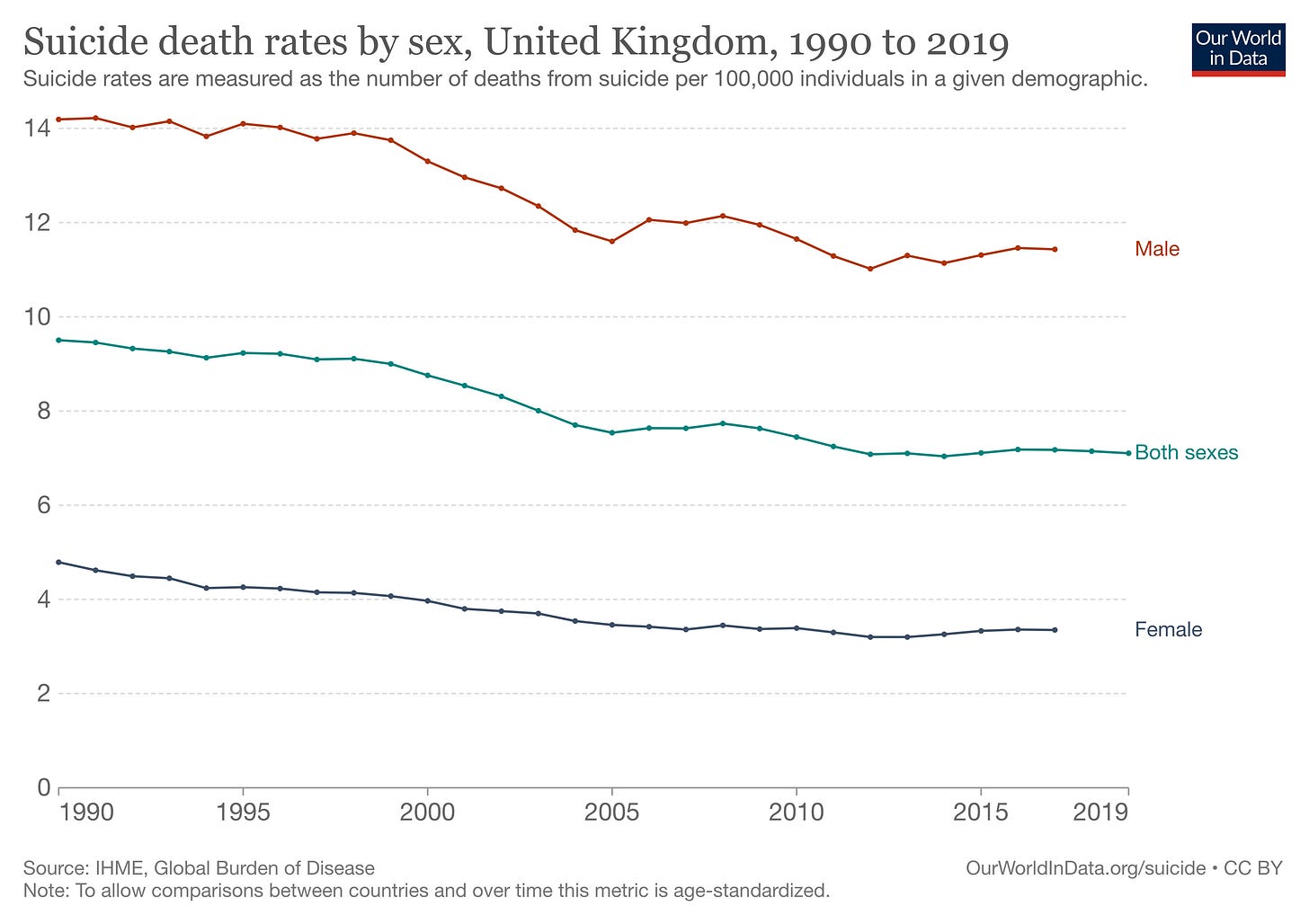

Suicide is the leading cause of death in young adults aged 20-34. In the UK, men have approximately three times the rate of suicide as women and the gender difference seems to be universal across all countries. The group with the highest risk of all are middle-aged men.

Almost 5000 people in England died by suicide in 2020. There will be even more families, partners and children devastated by the loss of a loved one. Globally, more people die by suicide than homicide. There is variation between countries, from 0.4% of deaths in Greece in 2019 to 4.5% of deaths in South Korea. Rates also change over time; most countries in Europe have seen a fall in suicide from 1990 to 2019.

…but it is complex for each individual

Perhaps counter-intuitively, given the global health burden, suicide is a relatively rare event at the individual level. In England the yearly suicide rate is 10 per 100,000 people. Even for mental disorders most commonly associated with suicide, like borderline personality disorder, over 90% do not die by suicide.

Suicide is a complex act with the potential of multiple contributing factors: mental health problems, relationship difficulties, deprivation, social isolation, substance misuse. There is rarely, if ever, a singular cause. The pathway that leads a person to contemplate suicide is unique to them. Almost three quarters of those who complete suicide are not in contact with mental health services. The majority (approximately 60%) of people who die by suicide deny they are planning to, when asked at an early time-point.

Assessing risk of suicide

When individuals are in contact with mental health services, their risk will be assessed at various time-points by clinicians. In a pertinent clinical example, a patient might present to their local A&E with suicidal thoughts or deliberate self-harm.

A comprehensive clinical assessment will include a judgement about risk of suicide. Patients who are thought to be unsafe leaving the department, may be offered an admission to a mental health hospital. Those thought to be at highest risk, may even have a nurse assigned to be with them continuously. Doing so is undoubtedly a restriction on a person’s freedom but we justify this by the belief that we are temporarily restricting their ability to end their life.

Another option is to discharge the patient, often with the support of a crisis intervention / home treatment team. This is a specialist service, mostly staffed by nurses and doctors who can provide daily support through an acute crisis, as well as providing treatment for any underlying mental disorder.

From working in London mental health services for a number of years, it is far more common for patients presenting with suicidal ideation or self-harm to be discharged with some form of community support. This is fortunate because suicidal ideation is relatively common and psychiatric hospitals wouldn’t have the capacity to admit everyone.

How a psychiatrist decides who is safe to go home and who would benefit from coming into hospital is a complex clinical decision based on their previous experience, interaction with the patient, the patient’s risk factors and personal circumstances. Much of it is based on intuition. National guidance specifically advises against using structured risk assessment tools to predict suicide risk.

Notably, we generally respond to perceived risk of suicide with short-term interventions - in the belief that the current crisis, like all things, will pass. For those with more longstanding, chronic risk of ending their life, interventions such as psychotherapy or certain medications (lithium), might be helpful.

Why suicide prediction is hard

We know risk assessment is hard but can we quantify how difficult? One way is to use Bayes’ Theorem to assess the usefulness of risk stratification. (If you have a spare 15 minutes, this 3Blue1Brown explainer video is worth your time.) It is used to calculate probability, incorporating new information with prior beliefs:

P(A|B) is the posterior probability, or the probability of A given B. For suicide prediction, this might be the probability of completing suicide in those categorised as high risk

P(B|A) is the probability of B given A, so the probability of being categorised as high risk in people who complete suicide

P(A) is the prior probability, or the baseline rate of suicide in the population

P(B) is the total probability of being classified as high risk (in total, for those who complete suicide and in those who do not)

The probability of completing suicide is directly related to the baseline rate of suicide. As I have stated, suicide is an infrequent event, affecting approximately 10 per 100,000 people over a year. Patients who present to A&E departments with self-harm will have a higher rate than this, (in the order of 450 in 100,000 in a year) but this is still infrequent, the equivalent of 0.45%.

If we consider the timescale of interventions we might use in response to acute suicide risk (like admitting to a psychiatric ward), the proportion who complete suicide would be even smaller.

As a result, even if a patient is classified as high risk, the probability of them completing suicide will be low (given this rate) even if the risk prediction is highly accurate.

Hypothetically, consider a near perfect suicide prediction tool that correctly categorises 99% of those who go on to complete suicide as high risk and incorrectly categorises only 2% of all those who do not complete suicide as high risk. If a patient is deemed high risk, what would their risk of completing suicide over a year be?

We can answer that question using the above equation:1

P(A|B) is the probability of completing suicide if categorised as high risk (what we are trying to work out)

P(B|A) is the probability of being categorised as high risk in those who go on to complete suicide = 99%

P(A) is the rate of suicide over a year in this population = 0.45%

P(B) is the total probability of being categorised as high risk (whether going on to complete suicide or not)

It is calculated as the probability of being rated as high risk in those completing suicide multiplied by the baseline probability of completing suicide, plus the probability of being rated as high risk in those not completing suicide multiplied by the baseline probability of not completing suicide (we know that if the probability of completing suicide over a year is 0.45% then the probability of not completing suicide is 99.55%)

Putting that together, P(B) = (99% * 0.45%) + (2% * 99.55%)

Let’s substitute the above into our equation:

P(A|B) = P(B|A) * P(A) / P(B)

P(A|B) = 0.99 * 0.0045 / (0.99 * 0.0045 + 0.02 * 0.9955)

P(A|B) = 0.18

Perhaps counter-intuitively, the probability of someone who has been categorised as high risk, by a near perfect assessment tool, completing suicide over one year is only 18% (i.e. more than 80% probability of not dying by suicide). The reason behind this is the low baseline rate of suicide.

But bear in mind that in the real world we’re never going to have a tool that accurately categorises 99% of those who complete suicide and only miscategorises 2% of those who do not complete suicide.

Furthermore, the baseline suicide rate, as mentioned above, is gradually decreasing over time. This is true even for people in contact with mental health services, where it has gone from 111.5 per 100,000 patients in 2005, to 63.7 per 100,000 patients in 2015.

Real-world data illustrates this further. In a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies following a suicide attempt (n>300,000), 5% of those deemed high risk completed suicide over a mean follow-up of five years - meaning 95% of those at high risk did not die by suicide.

What if a patient is judged to be at low risk of suicide, should that reassure us? Well, somewhat. According to the above meta-analysis, individuals characterised as low risk are roughly four times less likely to complete suicide than the high risk group. However, because so many more people are rated at low risk, approximately half of those dying by suicide had been classified as low risk.

My belief is that the rate of suicide over the short-term following a clinical assessment is too low to ever make suicide prediction useful, at the level of the individual. I am going to repeat the three points which for me make suicide prediction a fundamentally hard problem:

A large majority of ‘high risk’ individuals will not die by suicide

A significant proportion (almost half) of suicides are by individuals categorised as ‘low risk’

More accurate suicide prediction tools are unlikely to move the dial for 1 or 2

Strategies for reducing suicide

Suicide is a serious global problem. As I have argued, suicide prediction is difficult. We must therefore turn our attention to suicide prevention; working towards further reduction in suicide rates through a combination of public and mental health interventions. These might include reducing access to lethal means, providing adequate treatment of mental disorders for all members of society and having a robust care pathway for anyone experiencing a mental health crisis.

It’s a common misperception that when someone has decided to end their life, it is inevitable. In fact, restricting access to toxic medications, pesticides, frequently used locations or firearms is an effective strategy for reducing suicide rates. There is some evidence that over time we are making real progress on suicide prevention both globally and in the UK:

For those people experiencing non-fatal self-harm or suicidal ideation we should respond with compassion, treat any mental disorder and provide an individualised safety plan that does not rely on the false assumption we can make accurate predictions about their risk of suicide.

If the numbers going into the equation don’t make sense, please do go watch that 3Blue1Brown video which explains it much better than I can

Excellent article, thank you.

it's a great piece! but It also highlights the issue with suicide prediction is that what to do is still VERY NOT GOOD. I wrote about this recently,.recently...https://open.substack.com/pub/thefrontierpsychiatrists/p/are-we-telling-the-truth-about-suicide?r=1ct8f&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web