The case against 'mental health'

A shift away from mental illness may be doing more harm than good

Everyone, it seems, is talking about mental health.

In the UK, Mental Health Awareness Week is scheduled for May 13th, while October 10th is World Mental Health Day. We’ve already had Time To Talk Day in February, the perfect opportunity to start a conversation about mental health. For the students among you, there’s University Mental Health Day, during which you may be offered an app to track mood, stress, and sleep. For male readers, International Men’s Mental Health Day is in November.

These initiatives are part of a cultural change in how we view mental disorders. Rather than mental illness affecting a small proportion of the population, mental health is something we all have.

Celebrities are more open about their struggles with mental health. Though, almost universally, this tends to be common mental disorders like anxiety or depression, rather than severe mental illnesses like schizophrenia.

The shift away from discrete ‘mental illness’ to a broader ‘mental health’ reframes the conversation away from categories towards a universal spectrum. Is this change for the better? Let’s think it through and examine both sides of the ledger.

The case for mental health

The push towards mental wellbeing clearly has good intentions. Mental disorders are highly stigmatised and it is logical that more openness will reduce stigma. Rather than people with mental illness being seen as ‘other’, anti-stigma campaigns emphasise that mental illness can befall anyone and that we all have mental health.

Reducing the stigma of mental illness may allow people to seek treatment who would otherwise be put off. In particular, middle-age men have the highest rates of suicide and are a target of suicide prevention campaigns.

Another reason to be more open about mental health is in an attempt to intervene early and prevent the development of mental illness (though I am skeptical). Could awareness of mental health problems allow for treatment before problems deteriorate to the level of a mental illness? Perhaps interventions to improve mental health in everyone might even prevent the development of such conditions in the first place.

So, the promotion of mental health had many good intentions. It aimed to reduce stigma, improve mental health before the development of mental illness, and demonstrate that there is no clear distinction between those with mental illness and those without.

How has the focus on mental health worked out? Like many good intentions, there have been unintended consequences.

The case against mental health

The prevalence inflation hypothesis

Greater awareness of mental health is usually taken as a positive – what could go wrong with everyone ‘checking in’ on their own mental health? Well, a psychologist Lucy Foulkes1, has raised the possibility that mental health awareness could itself be driving-up rates of mental disorders.

She calls this the prevalence inflation hypothesis and has put it forward as an explanation for the apparent rise in mental disorders. There are certainly benefits from increased recognition of some conditions (for example bipolar disorder and PMDD have a notoriously long time for diagnosis).

However, more awareness of symptoms may lead people to seek help for problems they would otherwise have considered a normal part of life. Increased awareness could result in over-interpretation; pathologising what previously would have been considered normal.

Labelling mental distress as a disorder can be a self-fulfilling prophecy. The plausible example Foulks gives is someone experiencing anxiety, labelling this as an anxiety disorder, and consequently avoiding situations that may be anxiety-provoking (which tends to worsen feelings of anxiety in the long-term).

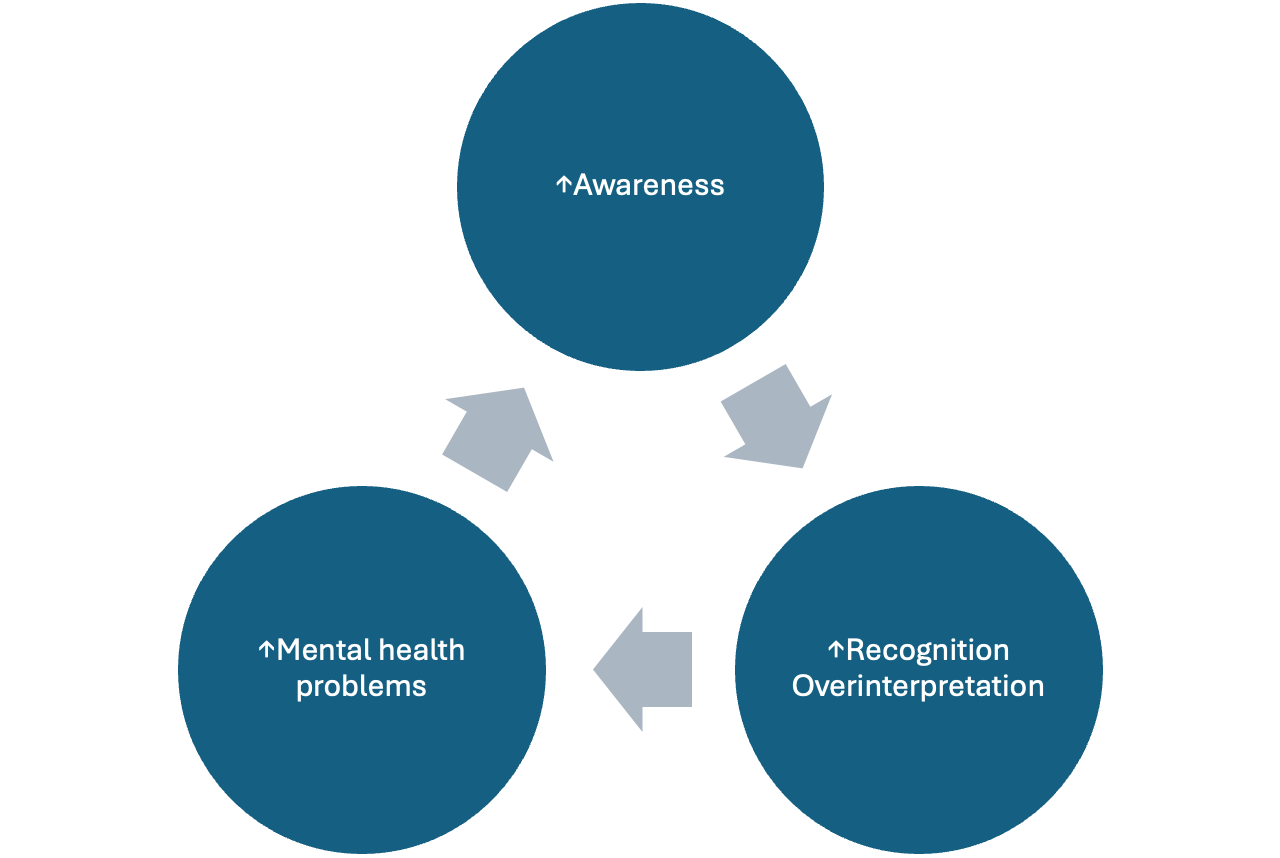

A positive feedback loop is formed, with greater awareness leading to increased labelling of problems as symptoms, leading to higher reported rates of problems, which in turn results in more public recognition.

As Foulkes herself declares, at the moment, this is still a hypothesis and needs to be empirically tested. However, when implementing change we should always be vigilant for negative consequences. Another intervention which sounds good on paper - improving mental health in schools - will be considered next.

School interventions

A strategy to reduce the burden of mental illness is to universally promote better mental health for all. One way to do so involves school-based interventions, like mindfulness, psychoeducation or CBT. Equipped with the right strategies, could young people avoid mental health problems in the future? So far, the evidence hasn’t been great.

Recently a large randomised controlled trial of mindfulness in schools was conducted. It did not show any benefit for mental wellbeing, functioning or depression. More worryingly, children who were already at risk of mental health problems did worse with the intervention compared to no treatment at all.

Perhaps the introspection of mindfulness isn’t actually useful or beneficial to everyone. That chimes with me. While exercises like mindfulness, or psychotherapy, may be helpful for some, they aren’t everybody’s cup of tea. By forcing us into the same mould a universal intervention can be harmful.

CBT-based interventions have similarly been associated with a worsening in symptoms. Foulkes has speculated that encouraging a focus on negative emotions is the mechanism behind these adverse effects.

While the jury is out on school-based interventions for mental health, at the very least, we must be alert to the possibility that they have a negative impact, particularly for those children most in need.

Has stigma really reduced?

One ‘win’ from the normalisation of mental disorders (remember, we all have mental health), must be reduction in stigma, right?

This may well be true for generic life struggles and perhaps for more common mental disorders like anxiety and depression. However, more severe illnesses (say schizophrenia, when a person might behave unusually, who may be muttering to themself on a bus or shouting in the middle of the street) remain as stigmatised as ever.

In some ways, placing mental illnesses on a spectrum of mental health, gives the wrong impression of genuinely severe disorders. These can’t generally be managed by opening-up, or mindfulness; the mainstay is powerful antipsychotic medication. Sometimes people are detained in hospital against their will. Under certain circumstances, they may even be forcibly injected with antipsychotics. In the midst of a psychotic episode, patients may believe others (often their carers or close relatives) are plotting against them. They may become violent, in response to these psychotic beliefs.

This extreme end of the mental health spectrum, if you do want to label it as a spectrum, is mostly absent from mental health campaigns. It is a less palatable side of mental illness for mass consumption and, unsurprisingly, is the most stigmatised.

If you want to see an unfiltered reaction to mental illness, look how we responded to the behaviour of Amanda Bynes or Britney Spears. Look at people line up to emphasise that mental illness doesn’t make people say racist or antisemitic remarks. Anyone who has spent time in a psychiatric ward will know this simply isn’t true.

Unfortunately, while ‘mental health’ has become less stigmatised, those with severe mental illnesses remain as shunned and misunderstood by society as ever.

False equivalence

There are other unintended consequences from the ‘we all have mental health’ narrative - a false equivalence of mental illness with the everyday struggles we all experiences. This has seeped into the discourse to the detriment of people living with severe mental disorders.

An example is the outrage at the UK’s unemployment figures with at least 20,000 people receiving incapacity benefits due to mental health conditions, more than two thirds of the total. The reaction to this in some quarters (the Guardian) has been wrongheaded and counterproductive. Rather than making the case that mental illnesses are illnesses and should be treated as such, they argue that people’s inability to work is an understandable response to neoliberal policies. Rather than being genuine conditions that you would seek treatment from a doctor, they argue anyone should be free to self-label.

Mental illness does carry more stigma than mental health but it remains a useful category. It provides an explanation as to why some people may be unable to hold down employment. Making a false equivalence between mental health struggles and disorders like schizophrenia is disingenuous and disadvantages people who are already among the most deprived in society.

Psychiatrists have expertise in mental illness not mental health

Perhaps the reason this all irks me is that psychiatrists aren’t actually experts in ‘mental health’. For sure, if you or a loved one is experiencing a psychotic episode – hearing voices, not making sense, believing that a microchip has been implanted in the brain – a psychiatrist is the right person to see. Psychiatrists are experts in dealing with conditions such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and severe depression. For more general advice about maintaining good mental health, I’m not sure we know much more than anyone else.

Trying to improve everyone’s mental health is certainly admirable. But we must focus resources, time and effort towards those who stand to benefit most. Those who at present are marginalised more than any other group - people with mental illness.

Disclosure, she is based in my current department and much of this post was inspired by a recent talk she gave

This is an excellent commentary on current society's overzealousness of focusing on "mental health" and the false equivalency with mental illness. To build on Foulke's prevalence inflation hypothesis, I might add that the overdiagnosis of certain disorders (e.g., anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, and ADHD) is actually exacerbating stigma for individuals who have the most severe phenotypes of these disorders. Those who have the most severe phenotypes of these disorders will be the most deprived of limited psychiatric resources and also have their diagnosis potentially trivialized. If everyone and their grandmother has ADHD ("if everyone has ADHD, then no one has ADHD"), then the value and meaning of the diagnosis effectively becomes watered down. It may be easy for said diagnoses to be met with a shrug if it seems everyone can get a diagnosis. I have seen this phenomenon in clinical practice, but have yet to come across a term that succinctly describes this. I am curious if you have come across any terms? My best attempt is to call it a "paradoxical stigma due to prevalence inflation."

As a patient I like this shift. Let me explain. The words health/illness, are too binary. We need something between health and illness, neither healthy or ill.

In physical health, we would call it lack of fitness. Someone very obese, or emaciated from starvation, walking with small shuffling steps, is not healthy, not fit, but also not necessarily ill.

That is where I am mentally. Unfit, not ill. Getting an anxiety attack from taking the bus, spending whole weekends in bed. But it is not at the illness level. I am basically functional, I drag my carcass to the office, work, do every second week parenting, and not thinking of any kind of self-harm. It sucks, but it is not serious suffering.

My mind needs to get fitter. Tried a couple of things that did not work, Quiteapin, magnesium, l-theanine, l-tryptophan, GABA. I will have a two month job gap and will try to get back into exercise, surely it will help but somehow I don't feel it will be a 100% fix. I don't even have any anxious or negative thoughts, not consciously.

At any rate, what my mind needs is not the mental equivalent of a hospital, as is the case of true illness, but the mental equivalent of the fitness coach.

BTW merging Asperger Syndrome with autism was a terrible idea. The Sperg is mostly just like being Mr. Spock from Star Trek, quite functional for an engineering job.

Similarly, my kind of not-ill-but-not-healthy depression and anxiety needs to be separated from the clinical one. If that was your point, I agree. But in that case we need both, not either-or, a concept of clinical illness and a concept of lack of health.