Our blessed science (their barbarous pseudoscience)

Lithium, suicide, and the dangers of a soldier mindset

Lithium is a bit special for psychiatrists. Despite being one of our oldest treatments, and a naturally occurring salt, we don’t know its mechanism of action. But we do know that it works, specifically for bipolar disorder, where it is still considered the ‘gold standard’ - recommended as the most effective long-term treatment. It achieved all this without ever being patented and therefore without the backing of a pharmaceutical company.

The story of lithium (brilliantly told by Walter Brown) is one of scientific breakthrough. It was discovered by an Australian, John Cade, who initially experimented on guinea pigs, then on himself, and finally on patients. Rather serendipitously, he found that it was beneficial for patients suffering from what was then called manic depression. His findings were initially published in 1949 but did not reach clinical practice until decades later.

Many psychiatrists (notably at the Maudsley Hospital) were initially skeptical about the efficacy of lithium. Aubrey Lewis called it ‘dangerous nonsense’ while Michael Shepherd described its research as having ‘dubious scientific methodology’. These doubts were overcome however, mostly through the work of a Dane, Mogens Schou, who led some of the earliest randomised controlled trials in medicine.

Psychiatrists hold lithium dearly, writing articles like Make lithium great again! and Lithium the magic ion. We see it take patients out of deep depressive episodes for which nothing else has worked. We see it giving patients stability in life. And we see its protective effect against suicide - a property widely seen as a fact in psychiatry. We theorise that lithium exerts this effect both through the treatment of affective illness and by a reduction in impulsivity. Remarkably, lithium levels in drinking water have been linked with lower population suicide rates.

But how solid is the evidence for these anti-suicidal effects? A recent meta-analysis from UCL’s Joanna Moncrieff cast doubt but was subsequently labelled as pseudoscience in a re-analysis published this month by Seyyed Ghaemi of Tufts University.

Into the meta-verse

Effects of lithium on suicide and suicidal behaviour: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials was published in 2022 in the journal Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences. As far as I can tell, it isn’t a ‘poorly vetted journal’ as Ghaemi claims. For what its worth, it has a bigger impact factor than the Journal of Psychopharmacology where he published his rebuttal.

The study looked at the effect of lithium on suicide (primary outcome) and non-fatal suicidal behaviour (secondary outcome). The results were essentially negative, there was no difference between lithium and placebo for either outcome. This was based on 12 studies with a total of 2.5k participants. The pooled suicide rate was 0.2% in the lithium group and 0.4% in the placebo group, which was not statistically significant (p=0.45). As you can work out, the actual number of events (suicides) was reassuringly small - two from lithium groups and five from placebo groups. In seven of the studies there were no deaths by suicide in either group.

I’m going to quote the study’s conclusion section in its entirely, because it is important not to mischaracterise the authors’ interpretation (bold is mine).

The evidence from randomised trials of the new millennium is inconclusive and does not provide support for the belief that lithium reduces the risk of suicide or suicidal behaviour. More data are needed to estimate the effect of lithium with more precision in general, and in subgroups of patients, specifically.

The psychiatrist who cried pseudoscience

Ghaemi’s response, The pseudoscience of lithium and suicide: Reanalysis of a misleading meta-analysis, is written provocatively. It immediately drew my attention because the language is outside the usual academic norms. He calls the authors pseudoscientists, based on the following definition.

This is certainly the case with the authors of this meta-analysis, whose apparent science is pseudoscience, not because of their methods, but because of their attitudes. Pseudoscientists deceive themselves, adhering to a set of unchanging beliefs. Then they can mislead honestly, based on their own self-deception. Self-deception is a precondition for deception.

He believes the authors have an agenda - to demonstrate that lithium (perhaps psychiatric medication more generally) doesn’t work and they will use the study to prove their point regardless of what the evidence actually shows. He really hammers this home.

This kind of article is not ‘research’ in the sense of new knowledge: it produced not a single datum of new fact. It is social activism disguised as science. It uses scientific journals as a public relations tool, providing a patina of respectability for explicit opinion-based propaganda on the internet and in social media.

Aside from the authors having an inherently biased attitude, he has two main substantiative criticisms in how they conducted their analysis. Firstly, they only included studies after the year 2000. They justified this on the basis that suicide events may not have been adequately reported in older studies, which seems questionable to me too.

The second big criticism is including studies in which no suicide events took place, either in the placebo or lithium group. Again this seems like a valid point. How can lithium show itself to be superior if no suicides took place in the placebo group? The authors justify this by invoking various references which recommend including these ‘zero event’ studies.

Finally, in one of the included studies, two deaths were apparently misclassified - they were wrongly reported as not being suicides. One of these was an opioid overdose, another was a death that was not labelled as suicide until more than a year after data collection was completed.

Ghaemi performs two reanalyses of the data, excluding studies which had zero events in either group. In the first, he uses Moncrieff’s numbers of two suicides in the lithium group and seven in the placebo group. The result is in the direction of favouring lithium but does not reach statistical significance - Odds Ratio 0.29 (95% CI: 0.08 - 1.08), p=0.07. He seems to interpret this as a positive result, mistakenly in my opinion.

Lithium is protective with odds ratio of 0.29, indicating 71% reduced odds of suicide. Confidence intervals cross the null but are mostly on the side that favors lithium indicating high confidence of a real effect.

A confidence interval crossing the line of no effect but mostly on the side of lithium does not indicate high confidence of a real effect! The p value alone tells us the result wasn’t significant. You can’t make up your own interpretation of statistical tests. That’s not how it works.

He then repeats the analysis with the two questionable suicide classifications (two suicides in the lithium group, nine with placebo). With these numbers, the result becomes statistically significant (p=0.02), with an odds ratio of 0.25, 95% CI: 0.08 - 0.83). Overall, it is interpreted as, ‘The anti-suicide effect of lithium is supported strongly by randomized clinical trials.’

To me, if the statistical significance of a result hinges on whether one or two deaths were correctly classified, the evidence is not robust; I am more in agreement with Moncrieff’s conclusion, more evidence is needed.

Wearing our identities lightly

While Ghaemi criticises decisions made in the analysis, his main gripe is that Joanna Moncrieff and those of her ilk are not objective. They have come to the belief that psychiatric drugs are harmful and seek verifying evidence. Scientists on the other hand, are impartial. Neutral. Disinterested. They base their beliefs solely on the evidence.

It is certainly true that Moncrieff has strong opinions about medication, some of which fall outside mainstream consensus. In a blog from 2015, she is strongly critical of lithium, which she refers to as a ‘neurotoxin’.

In 1957 a pharmacologist bemoaned the fashion for treatment ‘by lithium poisoning’. One day, I believe, we will wake up and realise his concern was spot on!

It is reasonable to question on how she evaluates the evidence for and against lithium. But no-one comes from a position of complete objectivity. Not really. Anyone who has committed blood, sweat, and tears to a meta-analysis will have some skin in the game. It may not be as explicit as financial game, or a clear idealogical position, but most researchers perform meta-analysis in service of their own pet theory.

We all have identities that will influence our interpretation of data: psychiatrist, psychotherapist, psychopharmacologist, patient, carer. It is the best we can do to wear these identities as lightly as we can.

I suspect that my worldview closes matches Seyyed Ghaemi’s. At the least we probably have similar view on psychiatric medication. It is because I identify with him, that I should be especially careful not to uncritically take his opinion as fact. Be wary when arguments or evidence seem to backup your closely held beliefs!

The garden of forking paths

Another issue worth delving into is Ghaemi’s description of meta-analysis (a framework for synthesising results across a number of separate studies) as being prone to pseudoscience.

Depending on which studies one includes, and which one excludes, one can prove any point one wants. The warning was sounded decades ago, when meta-analysis was new, by a founder of clinical epidemiology, Alvan Feinstein (Feinstein, 1995), and by the psychologist Hans Eysenck (Eysenck, 1994).

Now before we go further, I have to assume the citing of Eysenck is deliberately ironic. It has to be. As readers may be aware, Eysenck (now deceased) is now a cautionary tale of research misconduct, whose work has been declared unsafe.

Whether Eysenck was cited knowingly or not, it is true that the choices made in designing and conducting a meta-analysis can impact its findings. Which studies were chosen. Which were excluded. Which outcomes were chosen. How outcomes were pooled across studies. Which statistical models were used. We sometimes call these choices researcher degrees of freedom, or more poetically, the garden of forking paths.

More worryingly, we don’t always know which decisions were made after the numbers were crunched. Could researchers have analysed the data in various ways and then only published their favourite results? Sounds problematic, right. Especially when you consider, as I mentioned, that researchers usually have some vested interest in the results.

This type of problem is well recognised and there are two main ways to mitigate it.

1. Pre-registration. This is a tool to avoid researchers trying out different methods and going with the one that bests fit their hypothesis. It works by publishing the proposed methodology and analysis plan - crucially before conducting the study. Any deviation from the registration can then be scrutinised and the researchers held to account. Did Moncrieff’s meta use pre-registration? Yes, it is available here on PROSPERO. It seems to fit fairly closely to their published results, although they did some additional analyses using R, rather than just a simple one using SPSS that was planned.

2. Sensitivity analyses. Another way of dealing with a large number of possible choices is to re-do the analysis with different decisions. If you still get broadly the same results, these look more robust and more believable. This is especially important if some of the choices you made were questionable. And indeed that is what the authors did. They knew the decision to exclude studies before 2000 was debatable, so they re-did the analysis with the older studies and got similar results. They knew their statistical analysis would not please everyone, so they ran half a dozen different models and got the same results.

While the Moncrieff analysis may have been influenced by their prior beliefs about lithium, they have at least used safeguards to reduce the risk of this bias.

Soldier mindset

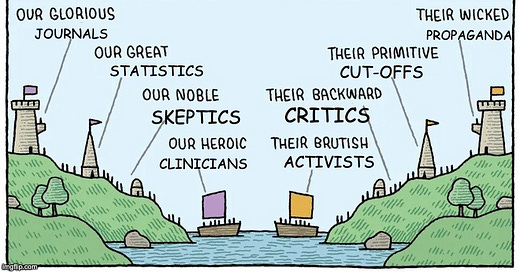

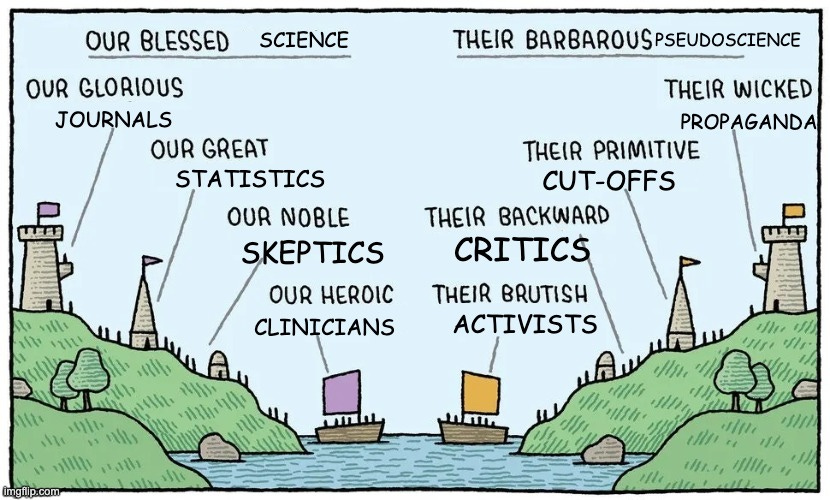

Ghaemi’s critique is an example of adopting the soldier mindset, alternatively described as my-side bias. In this scenario, evidence is gathered to prove a point against the other side. It is easy to fall into this mindset when a debate is polarised between two opposing camps - intelligent people are exceptionally good at gathering evidence and building arguments for their cause.

This attitude is less effective at actually getting at the truth. For this, we need to be aware of our biases, wear our identities lightly, and listen to the opposing side - described by Julia Galef, as the scout mindset.

In the case of lithium, I’m firmly on the side that it is an effective treatment for bipolar disorder. I can also acknowledge that showing whether lithium prevents suicide is exceptionally difficult, because suicide events are, thankfully, rare occurrences. All the debate about its effectiveness is based on such a small number of suicide deaths (n=9).

You don’t need to do a power calculation to know that nine participants is too small to form the basis of reliable evidence. Suicide is a complex outcome, for any individual it is extremely difficult to identify a single cause. I don’t think the evidence from randomised controlled trials can definitively prove that lithium prevents suicide and I’m not sure it ever will.

Obviously it would be nice if we could avoid the soldier mindset and judge evidence irrespective of whether it favours our side or not. But humans and their cognitive biases are difficult to overcome, is there a more structural way to avoid these battles in science?

Adversarial collaboration

One methodological innovation is adversarial collaboration. You get some researchers from one side of an argument and others from the opposing side to agree on a fair test of a hypothesis. The beauty of science is that any idea can be examined by experimentation - and, as you know, if your theory disagrees with experiment, it’s wrong!

Does it sound fanciful, that two researchers with opposing opinions would collaborate on an experiment that would prove one of them wrong? Well it happens all the time. You may remember my top paper of 2023 was a randomised control trial of antipsychotic discontinuation in schizophrenia. This trial was a collaboration between Joanna Moncrieff (skeptical about the benefits of psychiatric medication) and others such as Glyn Lewis and Thomas Barnes who are more representative of mainstream views in psychiatry.

This trial demonstrated that discontinuation of antipsychotics resulted in more relapses with no benefit in patients functioning. Essentially it disproved Moncrieff’s hypothesis and confirmed the long-term benefits of antipsychotics. For me though, her willingness to put her ideas to the test in collaboration with opposing researchers is the very essence of science; our blessed science.

My understanding is that the threshold for statistical significance - p = 0.05 - is a convention. Whilst by convention, p values 0.06 and 0.99 would fall short of statistical significance, the difference between these values reflects a gradient of evidence, not a dichotomy of 'significant' and 'not significant.' This underscores the importance of interpreting p-values as part of a broader context, rather than as definitive proof.

This is a very fair treatment of both sides, I think. The take home message is that we simply don't have enough data to comment on whether or not lithium is effective in preventing suicide.

Dr. Ghaemi has lectured to my residency class many times. He is clearly a very smart and well read individual, but "soldier mindset" perfectly describes his approach to disagreements. I have always been perplexed by his propensity to make excellent, valid criticisms of the opposing side, only to turn around and make statements like "actually p = 0.07 indicates high confidence of a real effect" which totally undermines his valid critiques.