How to read a paper

(Tommy's 2024 edition)

When scientists report their research, it is through an article published in a journal, a scientific paper. These papers, which follow a standard structure (Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion), are the foundation on which new scientific discoveries and inventions are built.

Despite this, there is little formal teaching (certainly in medical school) on reading such research. For those further removed from the sciences, papers can seem complex, inaccessible and even intimidating. With media reporting of science being frequently overhyped, evaluating research is an important skill.

The number of published scientific studies steadily increases year by year, despite science not steadily progressing. Much of what is published today is (arguably) of limited value to the scientific community - effectively ‘landfill science’. While there are diamonds amidst the dirt, sifting these depends on the ability to quickly digest the paper and make a judgement as to whether it is worth the time investment.

As a student, it was therefore a delight to stumble across Professor Trisha Greenhalgh’s guide to critical evaluation of medical research, How to Read a Paper. The book is a succinct overview of different types of papers in medical research and tips for evaluating them.

Inspired by this book, I’d like to think about reading a paper in 2024. The primary audience I have in mind are undergraduates but it is applicable for anyone with an interest in science, even without formal training.

How to read a paper

The depth of reading will depend on the purpose

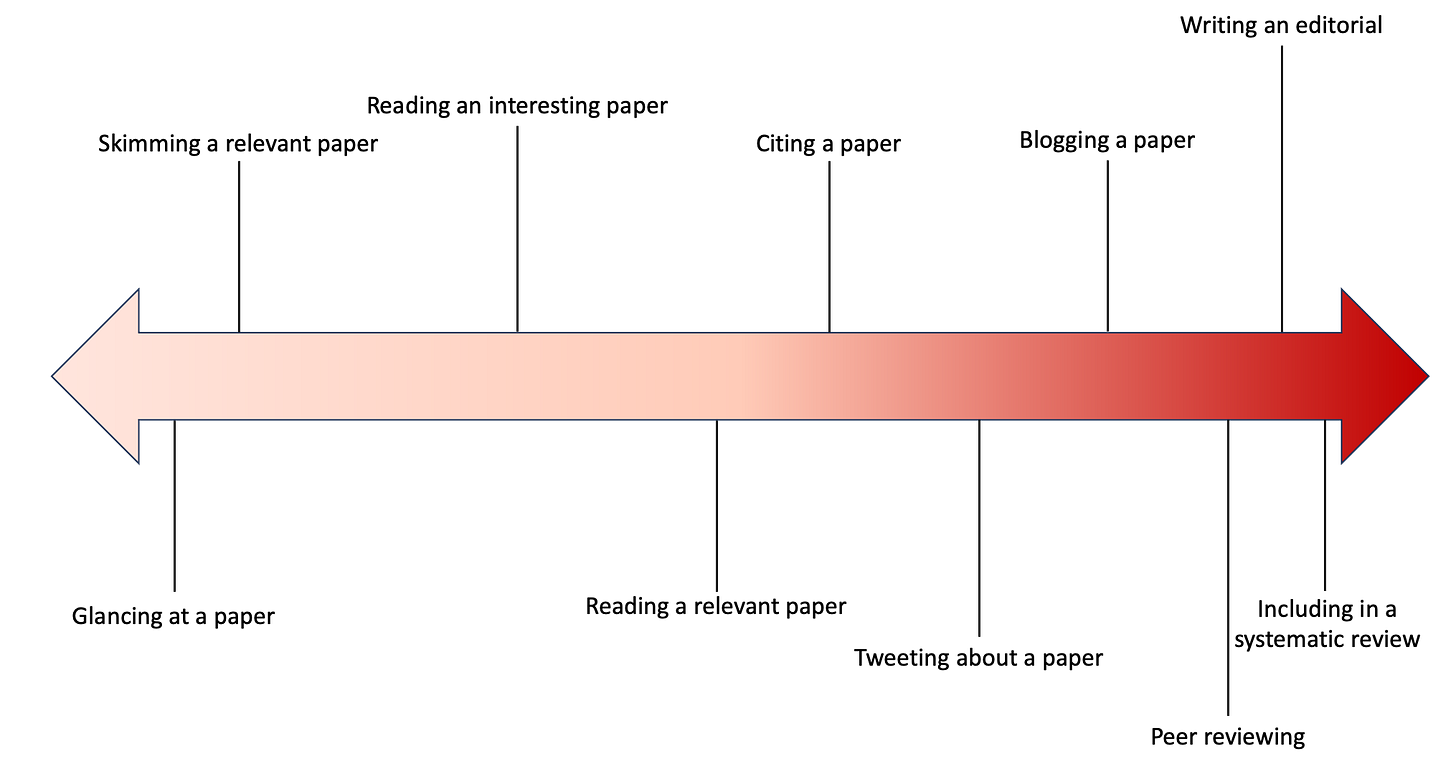

Is the paper being read purely out of interest, or to decide whether it should be published in a journal? Is it being cited in a systematic review, or being described in a blog? I have a rough spectrum in mind for how deeply to read a paper, illustrated below. Life is short. Don’t waste your time reading boring papers deeply unless obliged.

Greenhalgh’s How to Read a Paper goes into the different categories of studies within medical science (randomised controlled trials, cohort studies, case-control studies, etc) and how they should be evaluated. More broadly there are different types of scientific papers and these should be approached in different ways.

Those published in journals like Nature and Science tend to be a series of experiments each building on the last. To digest a paper like this can take several readings. Usually, they are accompanied by editorials or summaries which explain the key findings.

By contrast, if I’m reading a paper on a familiar topic in a more generic journal, I may be able to understand it after reading through once. I tend to look at the first paragraph of the Discussion first. This usually gives a short summary of the paper’s findings. I’ll then read through the Results which describe all the findings. In order to gauge whether these are trustworthy, I’ll go through the Methods - here should be stated exactly what they authors did and how they conducted their analysis. The Introduction and Discussion sections are largely superfluous but can put the research in the wider context - how it fits with the wider literature and implications for future research.

Making the most of the scientific ecosystem

So much can be gained by reading around a paper. Adjacent scientific articles, such as editorials can explain a paper and how it relates to other research. Letters to the journal may point out mistakes, overlooked aspects and opposing point of views. These traditional parts of the ecosystem can be staid, overly formal and reserved, though.

The emergence of new forms of media can be insightful in more straightforward words. These could even be from the paper’s own authors.

X (FKA Twitter). Everyone hates on X and the new ownership. Especially Substackers. I do too! But when it comes to circulating new science, it is unsurpassed. Where else do you find authors breaking down a paper into simple, digestible chunks? See Brenden Tervo-Clemmens describing the timing of executive function maturity. My favourite example of ScienceTwitter is the GWAS stories by Veera Rajagopal, here he describes how the obesity associated gene FTO was discovered.

Substack. This is the platform for getting into the detail. On this ketamine versus placebo under anaesthesia paper, there are different opinions from Scott Alexander and Awais Aftab...and me. Reading other people’s critiques can illustrate you how they evaluate research.

Podcasts. Long-form podcasts allow you to spend time with researchers, giving a lowdown on their work, the parts that will never be published in print. Listen to Nico Dosenbach discussing his discovery of the somato-cognitive action network , or Greg Clark going into his controversial study of the genetics of social status. You may have read Lee Cronin’s assembly theory paper in Nature, but have you seen him well up at the peer review process? Have you heard him describe this reminding him of being labelled with ‘learning difficulties’ as a school pupil?

Reading around a paper, especially through more informal media provides a lot of information. But sometimes you need to do the nitty gritty yourself. Maybe you’ve found a study you want to blog about; you need to go through it carefully. Let me tell you how.

Deep reading

Now you’ve chosen to read a paper in depth. This puts you in a tiny minority who go through the paper line by line. It puts you at a big advantage. You will pick up subtleties that someone casually citing a paper will never see.

The most thorough way to evaluate the methodology is with a checklist. These tools are available for every type of studies from randomised controlled trials to Mendelian randomisation studies. They are particularly useful when conducting systematic reviews but also outline the most important methodological pitfalls. Unfortunately they’re a bit boring for everyday use.

When you are orientated to the basic methodological considerations, I recommend going through everything associated with a paper with a fine tooth comb and a skeptical mindset. There is now more material associated with published papers than ever before. When going deep, try to get hold of everything you can.

Studies, particularly trials, will publish protocols ahead of the main results. If the research or analysis is changed midway through the study, this is a red flag. How can researchers get away with not adhering to a published protocol? Because most people don’t go into a paper in that much depth! In one case, I found that the sample size calculation had changed between the protocol and the published paper.

Was a trial negative, or just underpowered (too small to find a difference between groups). It’s actually pretty simple to do a power calculation, using the free software G*Power. This is what I did when evaluating a negative trial of raloxifene for schizophrenia, and I concluded that the trial was underpowered.

When evaluating a systematic review or meta-analysis, go back to the original studies and check whether they have been reported accurately. Mistakes happen more often than you might expect. In a meta-analysis of antidepressants in the menopause transition I found some errors, leading to the authors issuing a correction.

High quality studies will make their code and data available. Go back and check these. Do the data make sense? Does the code run? Does it give the expected results? Recently, a study claiming that hearing aid use reduced dementia risk in people with hearing loss was retracted. Why? Because the authors miscoded a key variable, which came to light after others tried to replicate their analysis.

Google the authors. Do they have conflicts of interest that affect how the results were interpreted? Were these declared in the paper? Eiko Fried highlighted in a recent trial of psilocybin that the lead author was the CEO of a psychedelics company, leading to the journal swiftly posting a correction.

Some errors will result in a paper being corrected or retracted. Others indicate a lack of methodological rigour. All show that you have gone through a paper thoroughly and contributed to the self-correcting mechanisms of science. Check everything you can. The supporting information, the appendices, the figures, the tables. Do numbers add up? Are they consistent? Is anything missing? Seek and ye shall find.

How to find papers

Finding interesting papers is a skill in itself. Again, the best place to find new research is X/Twitter. By following interesting people you can see a range of studies and the response to them.

Each month, I will look at the biggest journals in my field (British Journal of Psychiatry, Biological Psychiatry, World Psychiatry, Psychological Medicine, American Journal of Psychiatry, JAMA Psychiatry, Lancet Psychiatry, Schizophrenia Bulletin) to find new research.

Additionally, I have alerts when papers with relevant keywords or by relevant authors are published in PubMed. These get sent monthly and let me know about research just been published in journals or pre-print servers. These alerts mean that you could be the first to post about a paper.

For a wider range of papers, others will curate a monthly list for you. My favourite is Action Potentials by Andy McKenzie.

How to access papers

Annoyingly, when trying to read papers you may come across paywalls. Under no circumstances should you pay anything to read a scientific paper. This is because, in case you haven’t heard, academic publishing is a scam. Here are some ways of getting round this:

Become affiliated with a University. This is usually possible if you are a healthcare professional allied to an academic institution.

Check pre-print servers, such as medRxiv or BioRxiv. Authors may upload a pre-print at the time the paper was submitted.

Check ResearchGate. Authors sometimes upload their papers here.

Email the lead/corresponding author and ask for a copy (this is totally normal, and will not make you look weird).

Read, write, participate!

Practice makes perfect; the more you read, the more you sense what is plausible, what is iffy, and what is incredulous. Reading papers is a team sport, so participate and present at a journal club. It’s when describing a paper to others that I realise my understanding is superficial. And finally, consider writing a blog or post about the paper in question; you never know - your dissemination and analysis might provide the spark for a new scientific discovery or invention!

All the best for 2024 - I’m excited for the science that’s in store.

Lovely, comprehensive commentary. Am I concerned about damaging the academic publishing industry? For many reasons, not at all. The sheer amount of garbage that get published even in the most prestigious journals has done and continues to do enormous harm. The untold $billions of research funding money wasted on this bunk is a travesty. Likewise universities so focussed on quantity over quality.

Glad you mentioned checking out the $ conflicts of interest. For me, that is the second thing I check on a paper (after the title). If there are any fCOI, I regard it as nearly worthless. The influence of $ in psychiatry is massive, and the distorting effect on the research has been well documented by Erick Turner, Ed Pigott, Bob Whitaker, and many others.