Something about this infographic vexes me.

I find it implausible that half of dementia cases could be prevented by eliminating those risk factors, or that eliminating them is even possible. It is vague - what does ‘less education’ mean? The weighting of each factor is counter-intuitive. Do you really think that increasing HDL cholesterol is more important than excessive alcohol, obesity, hypertension and smoking combined. How many of these risks (like depression, social isolation or physical inactivity) could be explained by early symptoms of dementia, rather than causative factors?

Is the biggest risk factor for dementia really hearing loss?

The diagram is from The Lancet Commission on dementia prevention. The whole document is worth reading and it does contain caveats. However, it doesn’t fit easily into my own mental model of dementia.1

Dementia = Neurodegeneration

Dementia is not a disease but a syndrome, a collection of symptoms which are caused by several disease processes. All patients with dementia have commonalities: cognitive impairment and progressive functional decline. Dementia, sadly, gets worse over time and we can do little to halt its progress. The reason is that dementia involves neurodegeneration, loss of neurones and ultimately grey matter.

The most common disease process is Alzheimer’s dementia which is characterised by the build up of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. This starts in midlife but might not cause any detectable change in brain functioning for decades. The classification of this pathology (Braak staging) is based on the brain regions affected. Characteristically this starts in the medial temporal region and eventually spreads across the brain.

The next most common type is vascular dementia, caused by damage to blood vessels in the brain. This classically has a step-wise progression, with discrete drops in cognition and functioning. The management involves addressing vascular risk factors (such as smoking, high blood pressure and obesity) in an effort to slow further deterioration.

Less common causes include Lewy body dementia (which overlaps with Parkinson’s disease), fronto-temporal dementia and dementia associated with conditions like HIV, Huntington’s or Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease. Often patients can have multiple pathological processes; a mixture of Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia is frequently seen in clinical practice.

Dementia can be thought of as the final common pathway of these distinct pathologies - the presentation of an accumulation of brain loss which has built-up in the preceding years. Perhaps, like me, you are wondering how the above risk factors fit into the pathophysiology of dementia. Some, (particularly those relating to cardiovascular risk) make sense whereas others (like hearing loss) are more difficult to fit into a causative pathway.

Hearing aids

Hearing loss is robustly associated with subsequent development of dementia, with more severe impairment being associated with greater risk. Longer length of hearing loss is associated with greater risk. People with hearing aids are less likely to develop dementia than those with untreated hearing loss. The observational evidence for hearing loss is strong, leading The Lancet Commission to argue that implementing hearing aids to prevent dementia would be cost saving.

The mechanism by which hearing aids prevent dementia is not so clear. I can’t imagine it prevents the build up of Alzheimer’s plaques, Lewy bodies or small vessel disease. Is it possible that early pathological processes associated with dementia might also cause hearing loss (reverse causality). What’s more, the type of people who use hearing aids might be more likely to engage in other healthy behaviours like restricting alcohol use or regularly exercising.

As I’ve said before, observational research can only take us so far. In order to show causation, we need experimental evidence, i.e. randomised trials. One such study has been completed. It was large: n~1000 individuals with untreated hearing loss, aged 70-84. It compared hearing intervention to an active control (individual health education sessions).

The results were underwhelming. The intervention failed to beat control in the primary endpoint of cognitive decline at three years, though a pre-specified subgroup analysis, demonstrated a benefit for patients with greater risk factors for cognitive decline.

So while the observational evidence strongly shows that hearing loss is associated with dementia, we shouldn’t assume causation. The mechanism behind this association is not obvious and the empirical evidence to date is inconclusive.

Shingles vaccines

The latest hot-topic in dementia prevention is vaccines, specifically against shingles. Vaccines were mentioned only in passing by The Lancet Commission. They cite a meta-analysis showing that various vaccines are associated with decreased dementia but note that people who get vaccinated likely have different health behaviours than the unvaccinated. Since then, two landmark papers with quasi-experimental designs purport to show a protective effect of the shingles vaccine.

Varicella zoster is the virus that causes chickenpox. Following the primary infection, it lies dormant in neurones and can become reactivated later in life. This reactivation is known as shingles and presents with painful blisters. It can be quite debilitating, particularly in the elderly. Vaccines against varicella zoster can be given in childhood (to prevent chickenpox) and later in life (to prevent shingles).

While observational association of the shingles vaccine and reduced dementia risk is not very convincing, the rollout of shingles vaccine programmes has provided ‘natural experiments’ in which causation can be inferred.

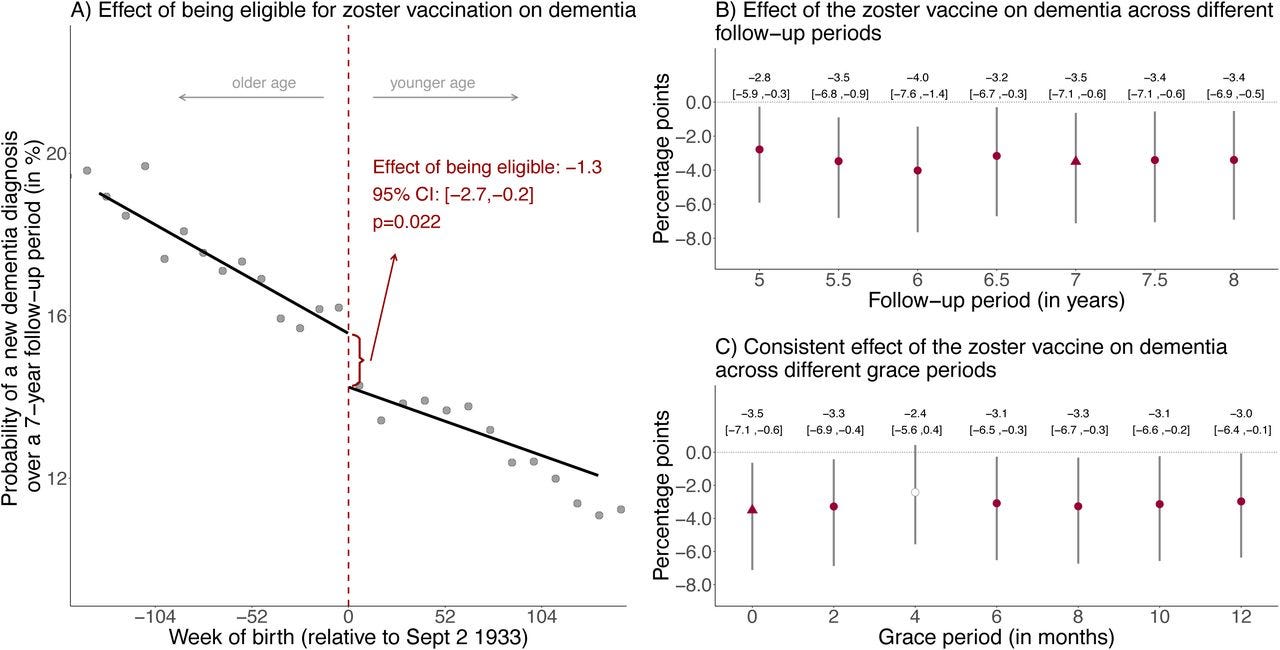

The first of these was published in Nature earlier this month (having previously appeared last year as a pre-print). The researchers took advantage of an age cut-off for shingles vaccination in Wales, which meant that people born before the 2nd of September 1933 were not eligible and never would be, whereas those born after that date were eligible. As this cut-off was arbitrary and we do not expect other systematic differences in people born just before or just after that date, it represents something akin to an experiment. It’s not quite a randomised study, but it is just about as close as we can get from observational research.

As expected, <0.1% of people born before the cut-off date received the shingles vaccine, whereas almost half of people born after that date were vaccinated. The group eligible for the vaccine had 20% less diagnoses of dementia in their electronic health record, compared to the ineligible group, over a seven year follow-up, as shown below.

The results were robust in a number of sensitivity analyses and were even replicated using death certificate diagnosis of dementia in England and Wales (currently available in pre-print). Slightly perplexingly though, the effect was entirely driven by women - as shown below, vaccine eligibility was not associated with reduced dementia in men.

You can read the authors’ explanations for this big sex difference (was it differential immunological response, off-target vaccine effects, differences in dementia pathogenesis or incidence) - let me know if you are convinced.

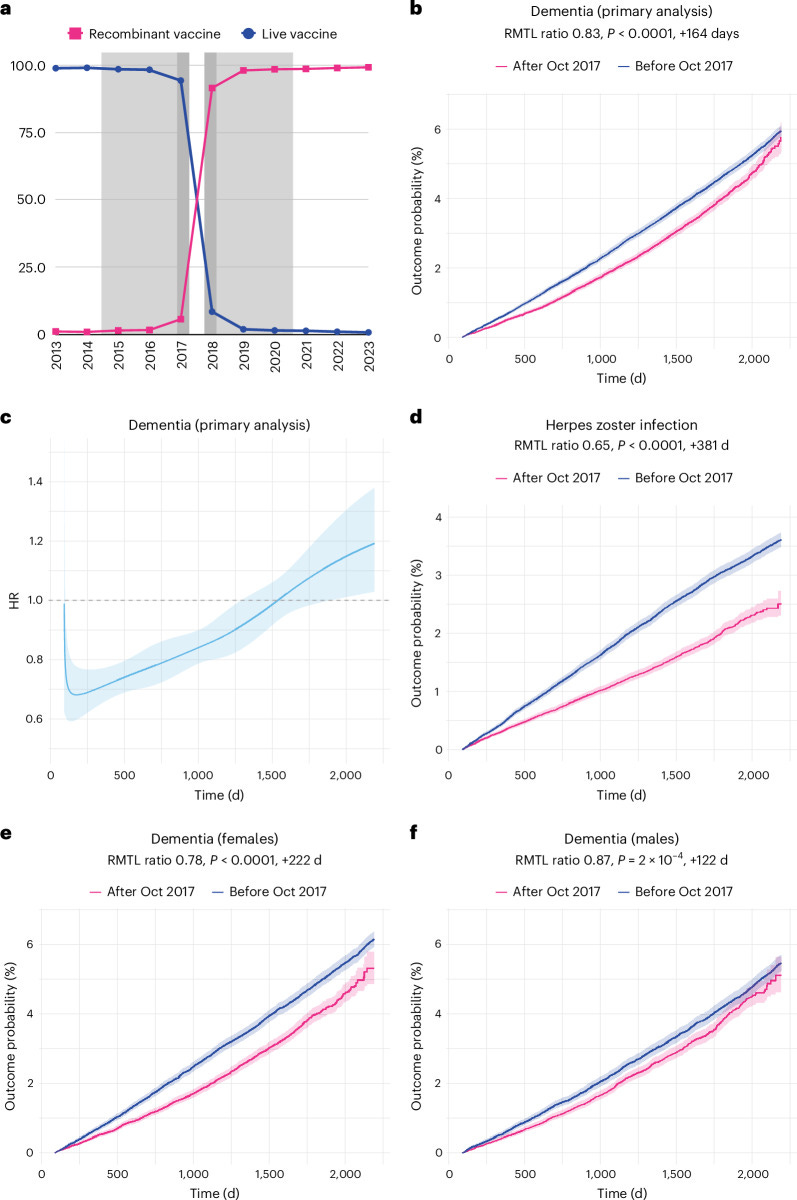

Like London buses, you wait for one quasi-experimental study of shingles vaccines, then they all turn up at once! A second but completely different natural experiment, using electronic health records was published last year in Nature Medicine.2 Here a different type of cut-off was used: in October 2017, the USA transitioned from the a live shingles vaccine to a recombinant vaccine, which offered greater protection against the virus.

Because this change was virtually overnight, the group receiving the live vaccine should not be systemically different from the recombinant vaccine group. As shown in Panel a below, the type of vaccine changes quickly and comprehensively between 2017 and 2018. In the group with the more effective vaccine, the incidence of dementia was lower, until five years when the curves converge (Panel b). In this study, there was a smaller effect in men (Panel f) but this was still significant.

These results are impressive and the clever study design eliminates a lot of the problems of confounding which plague observational research. Even though I would love for shingles vaccines to be a preventative treatment for dementia, again I have a couple of nagging doubts.

The first is that neither study shows a specific effect for any type of dementia (like Alzheimer’s or vascular dementia). When this was examined in the Taquet study, it showed very similar magnitude of effect for both these diagnoses. It makes me think that the vaccine isn’t directly affecting the underlying pathological processes that manifest in the syndrome of dementia but have a more general benefit on cognitive health.

The second is the timescale of the benefit. Look again at the Figure from Taquet 2024 above. The protective effect of the more effective shingles vaccine is evident in a reduction in dementia diagnosis within the first year of receiving the vaccine. However, we already know that the cumulation of pathology within the brain over decades eventually results in the symptoms of dementia.

What is going on? How can interventions such as hearing aids or vaccines, which do not appear to influence the pathophysiology of dementia have a beneficial effect on a much shorter timescale than these diseases take to develop. There is another concept in dementia research that may explain this. (Up to this point I’ve been keeping it, ahem, in reserve.)

Cognitive reserve as the mechanism

An interesting fact about dementia is that the burden of brain disease can affect people quite differently. For example, one person might have quite severe pathology, but be less impaired than another person with similar disease burden. The ability of a person’s brain to cope with such pathology has been called cognitive reserve.

The premise is that having higher baseline cognitive abilities allows a certain flexibility to cope with the loss of neuronal tissue and synapses. Factors associated with cognitive reserve include higher education, social engagement and exercise.

When discussing risk factors for dementia which are not causatively related to the underlying pathology (think depression, social isolation, sensory impairment), I believe effects on cognitive reserve is the likely mediating mechanism. These risk factors may deplete an individual’s cognitive reserve - meaning their mind is less able to cope with the burden of neuropathology.

I suspect the protective effects of the shingles vaccine have a similar pathway. If you’ve cared for elderly people, you may notice that a bout of illness, particularly if it involves hospitalisation, can really knock their functioning and cognition. Someone who is able to cope in their own familiar environment can decompensate rapidly in hospital. For some, it may be the first sign of dementia.

If you ask me whether Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia or Lewy body disease can be prevented by interventions like hearing aids or shingles vaccines, my answer is…probably not. But optimising our cognitive functioning through sensory aids, treating depression, avoiding infections like shingles, and remaining social engaged seems like a reasonable strategy to delay the cognitive decline associated with these diseases.

Such interventions might just increase our brains’ resilience to cope with the ravages of dementia and give us more time in good cognitive health.

I’m by no means an expert in dementia!

COI - the lead author is an esteemed colleague, Maxime Taquet

I'm not a neurologist OR a psychiatrist (tho sort of adjacent to/dabbled in some ways) so this is a more "constructionist" position, but your take really makes sense. The reserve/redundancy (cognitive and otherwise) must make a massive difference, and OBVIOUSLY it will be bigger in people with let's say more education and lower with people with emotional disorders (depression, PTSD) or, for that matter, hearing loss. Hearing loss also makes sense as the most visible one: language and its processing has A LOT of redundancy (we know how many letters can be missing from a text for it to be entirely legible; the effect is similar for speech, and it's also demonstrated by the fact that when listening to a language or even accent that's foreign to us, we typically need higher volume to pick everything up) but hearing loss removes this buffer. It will also affect social interactions.

And incidentally, I have my own (completely speculative) hypothesis for oft-touted "social contact being so very highly protective of dementia", which is that in addition to reverse causation you mention, there's also the fact that for the vast majority of older people, especially the very old, social interaction is likely the most cognitively demanding task they do. So it provides the training/stretching and building up of the reserve. It's not that "love" is necessarily better than writing philosophy articles, playing Bach, reading poetry or doing calculus, it's that very few elderly people do those latter things.

Have you read Charles Pillers new book on Alzheimer's research? https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/Doctored/Charles-Piller/9781668031247