As the days lengthen and you no longer have to get up in darkness, do you feel more energetic, happier, more purposeful? For some, Winter is a time of heightened risk for depressive episodes, with Spring bringing a new lease of life.

Almost a year ago, in my first Substack post, I wrote that making a diagnosis of Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD) relies on the timing of symptoms, more than their content. It is characterised by monthly episodes of affective symptoms, confined to the premenstrual phase of the menstrual cycle, but what about episodes that recur annually, confined to Winter months.

Could a vulnerability to cyclical relapses increase the risk for both these disorders?

Seasonal Affective Disorder

Diagnosis

The term Seasonal Affective Disorder was introduced in 1984, by Norman Rosenthal and colleagues from NIMH. They described a series of 29 patients, mainly with Bipolar Disorder, who suffered depressive episodes during Winter. They developed the Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire, a retrospective self-rated screening tool.

Although widely discussed by the media, NHS, and Royal College of Psychiatrists, Seasonal Affective Disorder is not a stand-alone diagnosis in either DSM-5 or ICD-11, unlike PMDD. Instead, it can be used as a specifier for Major Depressive Disorder or Bipolar Disorder with regular onset and remission of episodes during a particular season.

Both DSM-5 and ICD-11 exclude relapses that are thought to result from a seasonal psychological stressor - the example they give is seasonal unemployment, but the one that comes to my mind in the anniversary of a loved-one’s death. DSM-5 additionally requires that in the past two years, either manic or depressive episodes have been confined to a particular season, with no episodes of that polarity taking place at other times. It further specifies that over an individual’s life, seasonal manias or depressions substantially outnumber non-seasonal episodes.

In terms of symptoms, seasonal depressive episodes are characterised by oversleeping, overeating, weight gain and craving for carbohydrates. (Classically, depressive symptomatology consists of early morning wakening, loss of appetite and weight loss, though notably diagnostic symptoms for PMDD include overeating and oversleeping.)

Epidemiology

Hours of daylight correspond to changing seasons, with larger effects at the poles than equator. It was therefore, surprising to me that latitude was found to have, at best, a small effect on prevalence of Seasonal Affective Disorder, in North American or European samples.

Overall prevalence ranged between 0-10% across 20 retrospective studies. It seems to decrease with age and be approximately 1.5 times as prevalent in women than men (actually less than the female-to-male ratio in non-seasonal depression).

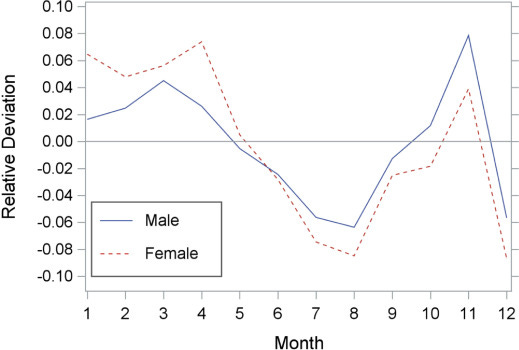

A systematic review found that manic episodes peak in the Spring/Summer, with bipolar depressive episodes, as expected, peaking in the Winter. While a large record-linkage study in Austria shows the seasonal variation in rates of psychiatric hospitalisation for depression (n=230,000), decreasing during the Summer months and increasing during Winter (with the exception in December, I assume, being due to Christmas):

Treatment

The initial conceptualisation of Seasonal Affective Disorder, included response to bright light therapy. With lower levels of daylight presumed to trigger depressive symptoms in vulnerable individuals, mediated somehow through circadian-mechanisms/melatonin/serotonin. I’m not sure I have a grip on the hypothesised underlying pathophysiology. (or whether anyone has) but for depressive episodes triggered by Winter, bright light therapy seems like a good bet.

Usual treatment involves 30-60 minutes of exposure to bright light each morning. Is this effective for Seasonal Affective Disorder? NICE are unconvinced, in a recommendation from 2009 stating that the evidence is uncertain. Likewise, a Cochrane review updated in 2019 found only one small RCT for the prevention of seasonal depressive episodes by bright light therapy.

I’m puzzled why the Cochrane review chose to only focus on the prevention of depressive episodes rather than response or remission of symptoms. If they had included the latter, many more studies are available.

One meta-analysis in 2005, found a significant reduction in depressive symptoms (effect size 0.84, 95% Confidence Intervals 0.60 to 1.08), based on eight studies. A more recent meta-analysis in 2020 was able to include 18 studies and found a smaller but still significant reduction in depressive symptoms (effect size 0.37, 95% Confidence Intervals 0.12 to 0.63). For reference, this is a similar magnitude to antidepressants for Major Depressive Disorder.

Light therapy does not seem to be specific for Seasonal Affective Disorder, it also works for non-seasonal depression with positive two meta-analyses in 2016 and 2020, as well as a Cochrane review from 2004. Admittedly, there are criticisms of the quality of these meta-analyses but it does pose the question whether Seasonal Affective Disorder is a distinct category if light therapy works for non-seasonal depression.

Seasonality and PMDD

By contrast, I think there is good evidence that PMDD merits its own standalone entry in DSM-5 and ICD-11. As I have previously described, randomised experiments show that fluctuations in ovarian hormones cause symptoms. While treatments like the combined oral contraceptive, work for PMDD but are ineffective for other forms of depression.

Whether PMDD shows seasonality is question that might tell us something about both disorders. It seem plausible that there is shared vulnerability to both monthly and seasonal biological cycles.

A 1997 cross-sectional study found that roughly a quarter of patients with PMDD reported marked worsening of premenstrual symptoms in Winter. An early small cross-over trial suggested light therapy might be effective for PMDD.

Praschak-Rieder et al. examined this from the other side - estimating the prevalence of PMDD in female patients with Seasonal Affective Disorder. They consecutively recruited 46 patients from a specialist Seasonal Affective Disorder clinic and 46 healthy controls (who were screened using the Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire to ensure they did not have seasonal symptoms).

Both groups then tracked PMDD symptoms over two menstrual cycles (which is the gold-standard for a diagnosis) during Summer months when seasonal depressive symptoms were in remission.

Only one of the healthy control group met criteria for PMDD, which is in line with the expected point prevalence of PMDD in the general population. Strikingly, 22 (almost half) of the Seasonal Affective Disorder group met criteria for PMDD.

My main quibble with this research is that the two groups were significantly different in age - the healthy controls were younger by ten years (mean age 23 versus 33). This could be an issue as PMDD has a tendency to worsen in the years approaching menopause transition.

Nevertheless it is an interesting preliminary finding that bears replication in a larger sample. It has clinical implications - if half of female patients with Seasonal Affective Disorder also have PMDD should we screen for it in this population? Could treatments specific for PMDD also have efficacy for Seasonal Affective Disorder? Do patients with co-morbid PMDD and Seasonal Affective Disorder respond differently to treatment? Do the two disorders share underlying pathophysiology?

The study was published in 2001. Since then…nothing. No replication has been published. In fact a PubMed search for PMDD AND ("seasonal affective disorder") shows there have been zero papers containing both these terms in the past four years.

What happened?

Another unrequited hypothesis

Unfortunately, like many scientific ideas, the link between SAD and PMDD wasn’t replicated or even disproven. It simply fell out of fashion. While PMDD is a growing field (2022 had the greatest ever number of publications), research into Seasonal Affective Disorder has steadily declined since its late 90s heyday.

Giving the example of the dexamethasone suppression test for HPA-axis dysfunction in depression, Professor Michael Browning notes that in psychiatry, hypotheses are rarely refuted. Instead, after initial hype is followed by underwhelming results, the zeitgeist shifts to new ideas.

I suspect interest in Seasonal Affective Disorder has wained after early enthusiasm gave way to skepticism among psychiatrists. As a result, we might never know whether half of patients with Seasonal Affective Disorder have co-morbid PMDD or whether there is a Winter worsening of PMDD symptoms.

Instead, the link between SAD and PMDD may well be added to the pile of unproven hypotheses lost to history.

>Strikingly, 22 (almost half) of the Seasonal Affective Disorder group met criteria for PMDD.

Could this be explained simply by the fact that having one "kind" of depression makes you prone to other kinds of depression?