Deciding what to research is the most consequential decision that a young scientist makes. There are roughly 80,000 working hours over the course of a career. How should that time be spent, given the almost limitless degrees of freedom?

Being a clinical academic (in my case, a medical doctor who also does research) helps narrow the focus. Doctors see unanswered clinical questions every day and have a sense of what matters to patients. How to choose which of these questions to tackle is seldom discussed though.

While this is written for the academically-minded medical student or junior doctor, I hope it has relevance for anyone thinking about a scientific career. I won’t discuss the structure of clinical academic training, which is readily available and summarised below. Instead, I’ll try to give the big picture view.

1. Find a specialty

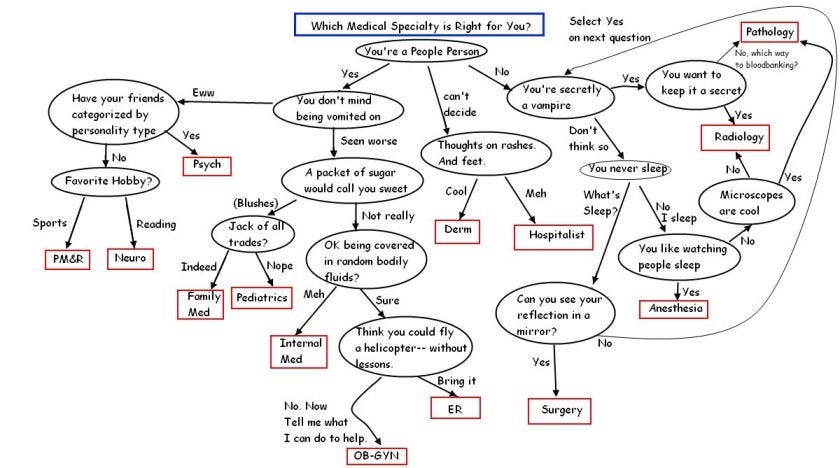

The first and usually easiest decision is choosing your specialty. Of all the decisions I’ll cover, this is most intuitive and therefore less amenable to rational analysis. Each medical specialty has a vibe and you can work out if it resonates with you during rotations. A nice part of medical training is sampling every specialty, in a sense getting to ‘try-on’ each career and finding out what fits.

Medical careers are varied and distinct; there isn’t a better or worse type, it’s all about finding your tribe. That being said, some careers are more conducive to research than others. Specialties with a laboratory component like pathology, virology, oncology, haematology, or clinical genetics tend to have strong academic links, as does public health. In contrast, working in emergency medicine or a busy surgical specialty doesn’t leave much time for research amid busy, anti-social work schedules. Psychiatry has both flexibility and a reservoir of unanswered clinical questions.

We can get more analytic for the other components of picking a research topic but to pick the right specialty, I recommend going with the vibes.

2. Find an institution

Deciding your academic location will greatly influence the research opportunities available in terms of the number of professors who could act as supervisors, internal collaboration, and funding options. Academia is a winner-takes-all system, whereby top institutions have higher probability of winning grants which perpetuates their advantage. If you can base yourself at a world-leading centre, it will open doors. Of course many people don’t have that luxury (for example due to family or caring commitments). If that’s the case, you might need to be more selective about your chosen field and to foster external collaboration.

For psychiatry, the largest UK research centre is the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience (IoPPN), which is part of King’s College London and closely tied to the Maudsley Hospital. Like many aspiring psychiatrists, I chose to train at the Maudsley in a large part due to the academic links. Somewhere as big at the IoPPN has experts in almost every area of psychiatric research.

The IoPPN doesn’t have a monopoly on success, there are various centres of excellence across the UK. For example, UCL is renowned for cognitive science and has collaborations with DeepMind. Oxford has fantastic links with basic neuroscience. Cardiff is a world-leader in genetics. No matter where you are, there will be some area of research in which the nearest excels. It might not be as comprehensive as the IoPPN or come with as many funding opportunities but success is possible no matter where you are.

When you have decided where you’ll be, the next task is to find a supervisor.

3. Find a supervisor

Like your institution, the reputation of your supervisor carries weight. When applying for fellowships, your supervisor’s track record in producing research and successfully mentoring academics will be taken into account. As with the institution, past success enables future success, whereby top professors attract more funding, more PhD students and more research output.

Not all professors are the same - they all play different roles and you need to find out what type suits you. There are always tradeoffs. Do you want someone who will guide you at every stage or someone who gives you more freedom to pursue your own interests? Senior professors may be able to offer more opportunities in terms of connections, funding and projects, while more junior supervisors may be more accessible and hands-on.

Identify who is doing the sort of research you’d like to do and get in touch. ‘Cold calling’ by email is perfectly acceptable. Don’t be put off on the basis of their seniority. Those at top often have a birds-eye view of the research landscape. Professors want interest from students, particularly if you can convey enthusiasm, initiative and drive.

Choosing a supervisor is important, I’d advise taking time, talking with supervisors and the students they supervise. Once you have an institution and have a supervisor, it’s time to really decide what kind of research to focus on.

4. Find a niche

You need to develop your own ideas, not just those of your supervisor. This is relevant when it comes to applying for doctoral fellowships - you will be awarded this on the back of your own application and performance at interview. Looking further ahead, the goal of a researcher should be developing independence, running their own programme of research. Deciding your research topic will define your PhD and beyond. While it is possible to switch areas, most academics work in a similar area to their doctorate.

Firstly, try to get as much experience with different types of research projects as possible - summer projects and intercalated BSc’s are good for this. Working in a lab is a completely different from sitting behind a computer doing data analysis, which is different from trying to recruit patients to take part in clinical research. Each of these suit different personalities and you won’t know whether you like it until you try.

In choosing what research question to tackle, I find the ITN framework helpful. This was developed by Open Philanthropy when deciding which causes to support, given finite resources. Each cause is supported based on their relative Importance, Tractability and Neglectedness. No cause will score equally highly on each dimension, but these metrics determine whether it gains support.

Importance. Your research topic should be pressing problem. In medicine, this is relatively easy to justify based on the number of people affected and the severity of a given condition. Schizophrenia, for example, is a serious mental disorder affecting 1-2% of the population that usually manifests when young people are on the cusp of adulthood. It often has life changing consequences affecting employment, relationships, and independence.

Tractability. How solvable is the problem? In the context of medical research, tractability might refer to the likelihood a treatment can be found. For disorders like schizophrenia, a substantial number will have an episodic illness pattern, meaning that symptoms will remit. While current treatment (D2 blocking antipsychotics) can help induce remission and prevent relapses, they don’t work for everyone and have problematic side-effects. Given some treatments are already available but aren’t perfect, better treatment of schizophrenia seems like a tractable problem.

Neglectedness. How many other people are working on this problem? If lots of funding is already going into a cause, each additional dollar has less value. There is a similar dynamic at play in research. For areas like cancer therapeutics, there are so many research groups working on the problem that each additional researcher is unlikely to add much more value. This is despite cancer being evidently important (a leading cause of death) and evidently tractable (some cancers can be effectively controlled or prevented).

Finding a cause (or in our case a research area) that is Important, Tractable and Neglected is the holy grail. A successful example is obesity. It is clearly important (affecting a large proportion of the population, with various negative health impacts), tractable (we can pharmacologically suppress appetite) and until recently was neglected. Now the advent of GLP-1 analogues has revolutionised treatment and has been an enormous success for the pharmaceutical industry.

5. Find your edge

An intrinsic part of academia is competition with others for limited research funding. Invariably, these competitors will be equally smart, industrious and conscientious as you, if not more-so. It is therefore crucial to find your edge, the thing that sets you apart from the crowd. In my view, this is the most important and difficult aspect of your research career to determine but there are some analogies from the world of business.

In his notes on startups Zero to One, the entrepreneur Peter Thiel makes a distinction between two types of new businesses. One is a copy of a successful model, which he calls 1+n. The paradigmatic example he uses is restaurants. There will always be another neighbourhood restaurant to add onto the existing number. The problem is they’re competing with all the other neighbourhood restaurants. As a result, margins are tight, wages are suppressed and profits are usually low.

Instead of trying to get a slice of a saturated market, it’s much better to create a completely novel business model (he calls this 0 to 1), effectively monopolising the market by offering something different from competitors. Google did this for search. Tesla for electric cars. Uber for taxis. Airbnb for holiday stays. Amazon for online shopping. If you don’t have to worry about reducing marginal costs to compete with identikit businesses, you have more room to innovate and expand.

There are parallels between startups and research programmes. For both, you are asking an investor or a funder to provide up front resources in exchange for what you promise to achieve. Like the business world, research funding is highly competitive. In both cases these are investments in you and your vision. As most startups fail, so most research projects do not deliver the transformational change they promise. It thus makes sense for both investors and funders to support a wide range of projects, in the knowledge that while many will fail, one could be world-changing.

Trying to iterate on successful projects puts you in a crowded marketplace. You’ll be competing against researchers in terms of funding and in publishing your research. A more appealing strategy is to do research that’s completely different from what’s already out there. This may be higher risk (you have less indication of what will actually work) but if successful you will be in a position to monopolise an area of research.

Another concept from economics that fits well with the competitive world of research is comparative advantage. This refers to the ability to produce goods at a lower cost than competitors. In research, think of this as the abilities you have that others don’t. In fields like neuroimaging and genetics, some researchers will have the comparative advantage of a technical background like physics, maths or engineering, which can prove useful in the analysis of complex data. If you are going to compete in such fields you have to find your own advantage, something that sets you apart.

Clinicians have one obvious advantage, by treating patients they have a practical sense of which solutions are likely to be successful. In a way, any time you see patients, you are able to do mini hypothesis-testing and see what is realistic. Over time, you get an understanding of disease that isn’t described in textbooks or academic papers.

Another way to gain a comparative advantage is to put yourself at the centre of overlapping fields. This can give you truly distinctive expertise. Most researchers are very knowledgable within their field but it is less common to look beyond their own area. For example, few psychiatric researchers additionally have experience in immunology, despite the immune system being implicated in mental disorders. Combining skills in psychiatry with another specialty, like neurology, radiology or endocrinology can likewise provide an advantage that helps you standout from the rest.

The more unique your skillset, the more people will think of you when they require those skills. Pick skills which are valuable and durable for the advantages to compound over time. Erik Torenberg describes this as building your personal moat.

6. Go your own way

This post reflects my personal perspective as someone still on the journey to being an independent researcher. Take my advice with a pinch of salt. In addition to conscious decisions, finding your place in academia involves personal trial and error, as well as luck. Developing a successful independent research program requires a degree of nonconformity - so feel free to ignore advice and go your own way.

If you have differing views or additional tips for choosing research topics, I'd love to hear it.

Dear Thomas, thank you very much for this excellent and insightful read. I particularly appreciate the idea of a niche where, in addition to psychiatry, you can stand out by having expertise in another field. I have observed that in medical school, we are often not trained to think in systems, which could be another area that might be useful.